Blog

20 January 2026

T is for…Tankards

Emmanuel’s plate collection contains several seventeenth-century tankards, a term then applied exclusively to mugs with a hinged lid. The earliest reference in the archives to one of these heavy pots occurs in 1620, when ‘Dr Branthwaites guilded Tankard’ is listed in a plate inventory. William Branthwaite, sometime Fellow of Emmanuel, was Master of Caius College at the time of his death, in 1619. Under the terms of his will, he bequeathed to Caius and Emmanuel identical drinking mugs, described as a ‘silver tankard pott, gylte, with my armes on it’. Emmnanuel’s early seventeenth-century ‘Benefactor’s Book’ assigns Branthwaite’s ‘chalice’ a value of £8, so it is not surprising that the tankard was stored in the Treasury, with other precious silver-gilt ware. Pewter tankards became widely used by students and Fellows alike during the 1620s, and many are listed in college plate inventories under the name of their owner (every member had his own personal drinking vessel). By the late-seventeenth century, though, unlidded ‘quart cans’ were becoming the fashion. This change in taste, as much as wear-and-tear, eventually led to nearly all the college tankards being melted down and re-fashioned. Branthwaite’s precious silver-gilt pot managed to survive until at least 1818, but it had gone by 1843. Half a dozen or so tankards did, however, escape the crucible. Ranging in date from 1675-1765, they are all inscribed with the names of their student owners, or rather donors, as the individuals involved were fellow commoners, who were obliged to present a piece of silverware to the college soon after their admission. Tankards enjoyed a renaissance in the nineteenth century, when they became popular as student sporting prizes. Several such trophies are held in the college Museum collection, including the Trial Eights tankard of 1875 pictured above.

T is for…Tunnel

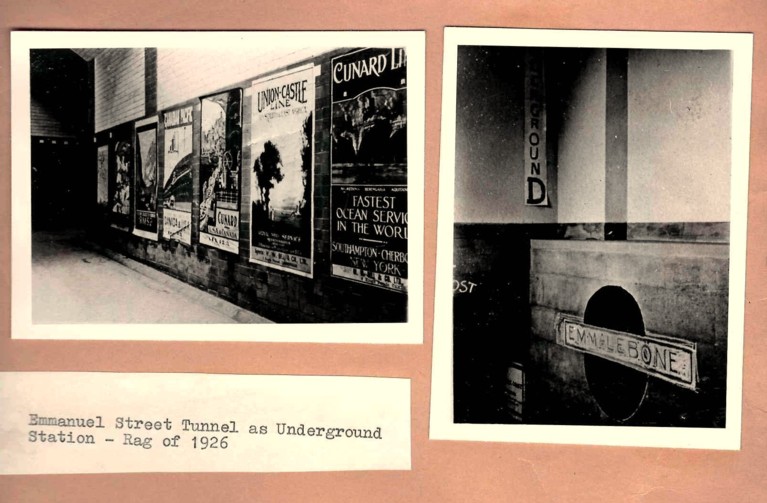

Emmanuel is thought to be the only Cambridge college to have an under-road tunnel. Lined with Edwardian green and white glazed ceramic tiling, it is a much-loved feature of the college. The tunnel was constructed in conjunction with North Court, in the years immediately preceding the First World War. The City Council had previously agreed to sell Emmanuel Street to the college, so that the planned new court could be seamlessly integrated into the college precinct, but a change of policy resulted in the council providing a tunnel instead. Incidentally, the architect of North Court, Leonard Stokes, invariably referred to the underpass as a ‘subway’, presumably because it was intended solely for pedestrian, and not vehicular, use. In the mid-1950s, however, the college started calling it a ‘tunnel’, and this is now the preferred term. When Emmanuel Street was widened in 1968, the underpass had to be extended at its northern end, and although the new tiles matched the originals as closely as possible, the join is not difficult to spot. The dramatic possibilities offered by the tunnel’s echoing acoustics and diagonal orientation have not been overlooked. A theatrical production, Roseleaf, was staged there in 1993, and the tunnel also served as part of the ‘Northern Line’ for the 2013 May Ball, the theme of which was ‘Last Call to London’. The tunnel’s resemblance to a London Underground station had been exploited as early as 1926, resulting in ‘one of the best rags ever perpetrated’. During the Long Vac, a group of Emma medics decorated the underpass with genuine railway posters, procured from Cambridge station by Julius Summerhays (1925). A mock station sign, ‘Emmalebone’, was painted directly onto a wall (see image above). This proved difficult to remove, earning Summerhayes an ‘avuncular’ rebuke from the Senior Tutor, P.W. Wood.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

15 January 2026

The turn of the year always brings a quiet magic to the gardens at Emmanuel College. January may appear subdued at first glance, but beneath the bare branches and winter light there is already a sense of anticipation. For the gardening team, this is not a dormant time so much as a reflective and preparatory one - a moment to take stock of the year just passed and to set intentions for the season ahead.

Winter reveals the underlying structure of the gardens more clearly than any other time of year. The bones of the landscape - avenues of trees, clipped hedges, borders and lawns - stand out without the distraction of summer abundance. It is a valuable opportunity for us as gardeners to assess balance and proportion, to consider where planting has succeeded and where it might be refined. Pruning fruit trees, roses and shrubs is a major focus now, carried out carefully to encourage healthy growth and good form later in the year.

Despite the cold, there is plenty of life to be found. Snowdrops are beginning to push through the soil, offering those first hopeful flashes of white and hellebores are quietly coming into their own, unfazed by frost. These early-flowering plants are always a morale boost - not just for visitors, but for the team as well. They remind us that the cycle is already turning.

Winter is also a time for groundwork, both literally and figuratively. Soil care is central to everything we do and where conditions allow, we are improving beds with organic matter to support the coming year’s growth. Elsewhere, we are repairing edges, maintaining paths and ensuring that the gardens remain welcoming and safe throughout the wetter months.

Planning plays a major role at this time of year. Seed catalogues are well-thumbed, planting plans reviewed and ideas discussed. At Emmanuel, the gardens serve many purposes: they are places of beauty and calm, working spaces and settings for study, reflection and community life. Balancing tradition with thoughtful evolution is always part of the conversation. We aim to respect the character of the College gardens while responding to changing conditions, including the realities of climate and sustainability.

Sustainability continues to guide our decisions. We are increasingly mindful of plant choices that are resilient and supportive of biodiversity and of gardening practices that work with nature rather than against it. Winter is a good moment to review what has worked well in this regard and to look for opportunities to do better in the year ahead - whether through habitat creation, water management, or planting for pollinators across the seasons.

The quieter months also give us time to reflect on how the gardens are used and experienced. Emmanuel’s gardens are an integral part of College life, offering space for solitude as well as shared moments. Seeing students, staff and visitors enjoying the grounds throughout the year is one of the most rewarding aspects of our work and it shapes how we think about the future.

As Head Gardener, I am always grateful at this time of year for the dedication and skill of the gardening team. Winter work is often unseen, but it lays the foundation for everything that follows. The care taken now - in pruning, planning and preparation - will be evident when spring arrives in earnest.

As we move into the new year, we look forward to sharing the gardens with you as they unfold through the seasons. There is much to come and it all begins here, in the stillness and promise of winter.

Best wishes

Brendon Sims (Head Gardener)

10 December 2025

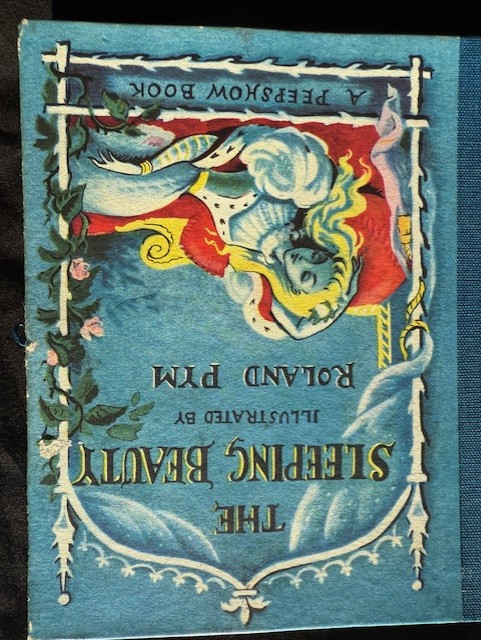

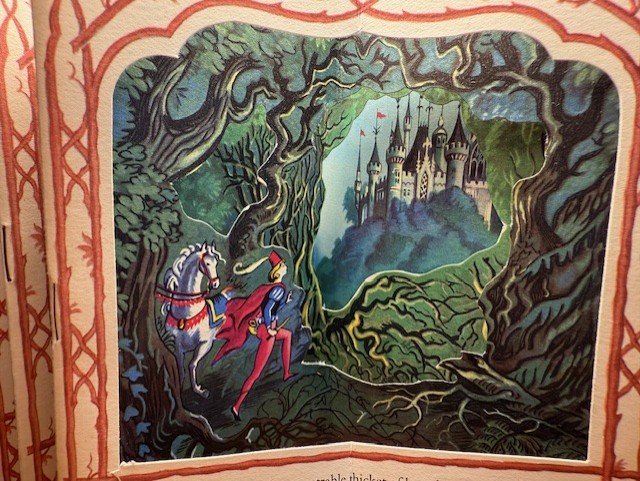

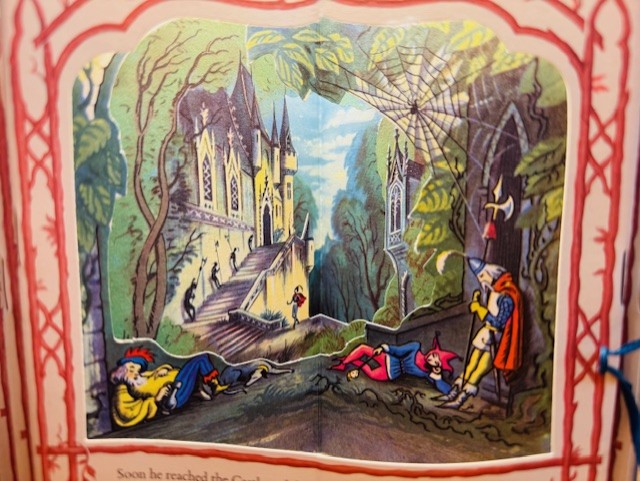

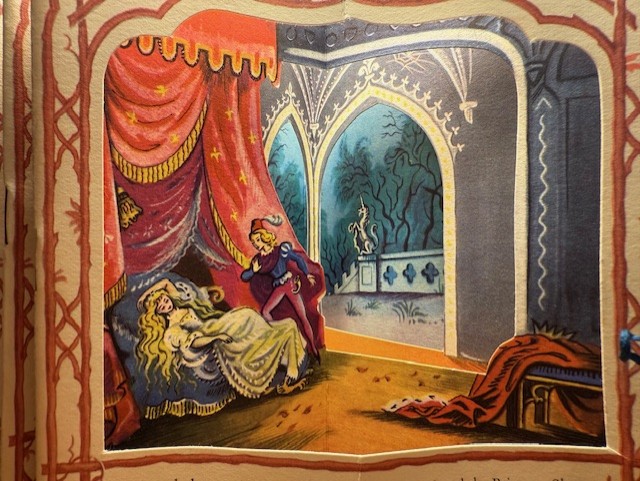

The panto season, along with other seasonal observances, is almost upon us. The spotlight this month on items in Emmanuel’s illustrated book collection is upon a curious and self-styled ‘peepshow book’ about Sleeping Beauty, produced in 1951 for the young at heart of all ages. Dating to the year of the Festival of Britain, this work by the illustrator Roland Pym (1910-2006) shows something of the same mid-century aesthetic. It involves an intricate folding structure in order to tell the familiar fairy tale in six scenes.

.jpg)

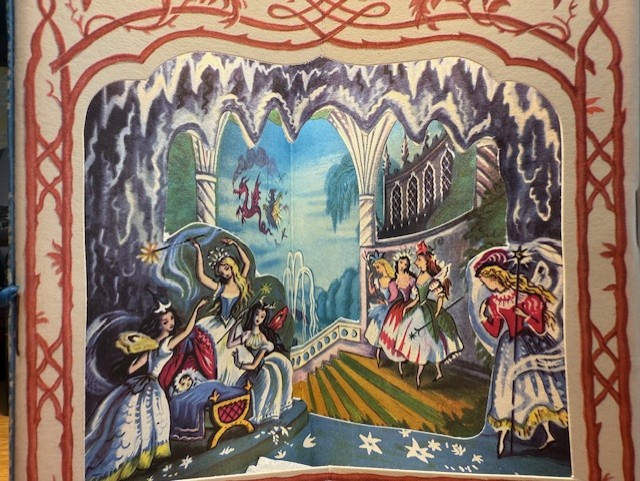

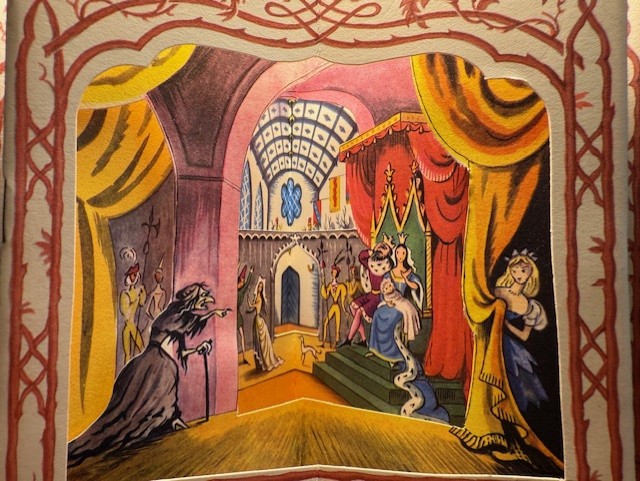

Each scene is comprised of four layers. Every picture has a frame bearing the text. Inside this are two folding sheets with cut-outs one behind the other, and then a background, so as to create an impression of a three-dimensional scene in a dramatically retreating perspective.

So in this first scene a King and Queen invite seven godmothers to their daughter’s christening, and six bestow attributes and accomplishments. On the left of the second folding layer are three fairies with the baby Princess, and on the right the seventh fairy looks on, while on the second folding layer are the other three fairies. But suddenly a chariot appears in the sky (painted on the fourth, background layer), with a wicked old fairy, angry at not being invited.

The wicked fairy issues a curse that at sixteen the princess shall prick her hand on a spindle and DIE. Cue horror! The King and Queen (on their thrones in a Gothic great hall) order all spindles to be destroyed in their kingdom, but the seventh fairy steps forward and modifies the curse: the Princess will not die but sleep for one hundred years and only be awakened by a King’s son.

On her sixteenth birthday the Princess opens a secret door to a room where an old woman sits spinning. When the Princess tries her hand at spinning she pricks her finger and falls at once into a deep sleep, as does everyone else in the castle, but the fairies appear and carry the sleeping Princess to a great bed.

Impenetrable thickets of brambles and trees spring up around the castle. One hundred years pass by, until a Prince, out hunting, hears the tale from an old peasant woman. At once the Prince resolves to waken the Princess and the thicket parts as if by magic to let him pass.

Inside the castle the Prince finds everyone, including the dogs, slumbering where they were when the Princess fell asleep. There are giant spider’s webs around.

The Prince duly finds the Princess, and when he kisses her she awakens with a smile. The spell is broken and everyone wakes up. All the good fairies come to the wedding of the Prince and Princess, who live happily ever after …

During his long life Roland Pym was a painter of murals, often compared with the more celebrated Rex Whistler, and designed the decoration of the Queen’s Retiring Room in the temporary accommodation at Westminster Abbey for the Coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953. He worked as a theatrical designer of sets for plays and operas, but saw his romantic style go out of fashion, although he continued to receive commissions, and also worked as a book illustrator for the Folio Society.

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

8 December 2025

As another year draws to a close and winter settles gently over Emmanuel, it feels like the right moment to pause, look back and appreciate all that has unfolded in the gardens over the past twelve months. The cycle of the seasons always brings its share of surprises, challenges and small triumphs and 2025 was no exception.

A Year of Weather in Extremes

If one theme defined the year, it was the long hot dry spells. Our borders, however, rose to the challenge. The herbaceous displays along the Paddock and Fellows’ Garden filled out beautifully once temperatures settled, rewarding patience with generous colour.

Notable Highlights

• Herbaceous borders: This year’s borders were packed with colour and variety. It started with a strong show in the Spring with Peony’s and other spring bulbs and continued into Summer with the Roses and Salvia’s, Delphiniums and Sysyrinchiums. The Autum held on to its colour with the Eupatorium’s and the Hylotelephium.

• Community Garden successes: The good sunny weather meant that we had plentiful crops this year, starting with the onions and garlic planting, right through to harvesting the many pumpkins and squashes deep into late Autumn.

• Lawns and new students: The lawns bore up admirably under a busy conference season and another enthusiastic influx of freshers. The team’s efforts in autumn scarifying and over-seeding should pay off handsomely when Spring returns.

It was fantastic to provide yet another garden tour at the end of November. It was well attended with a good blend of new students and a return of members. It was a pleasure to show you all around.

Projects and Improvements

The team undertook several behind-the-scenes improvements that will continue to benefit the gardens long beyond this season:

· Continued soil-health work in the Herbaceous Borders, particularly mulching with our own leaf-mould.

· Expansion of wildlife-friendly zones, including additional log piles and nectar-rich planting.

· Ongoing renovation of older shrub areas, bringing in fresh structure while preserving character.

These quieter, less visible projects are often the ones that shape the future of the garden most meaningfully.

The Team

No review would be complete without mentioning the wonderful gardening team whose skill, humour and persistence keep the college grounds looking their best. From early-morning mowing to wet-weather pruning, from glasshouse seed-sowing to the endless battle with weeds, their work forms the rhythm of the college year as surely as the academic calendar.

Looking Ahead

Winter offers us the gift of planning - time to sketch next year’s borders, consider new plantings and prepare for the first signs of snowdrops. There are exciting developments planned for the coming year, including further enhancements to the Fellows’ Garden borders and the arrival of the newly planted Camassia bulbs in North Court.

A Final Word

To all students, staff, Fellows and visitors who have paused to admire a border, ask a question, or simply enjoy a quiet moment in the gardens: thank you. These spaces are at their best when they are lived in and loved.

Wishing everyone a peaceful Winter and a flourishing year ahead.

Brendon Sims (The Head Gardener) Emmanuel College, Cambridge

5 December 2025

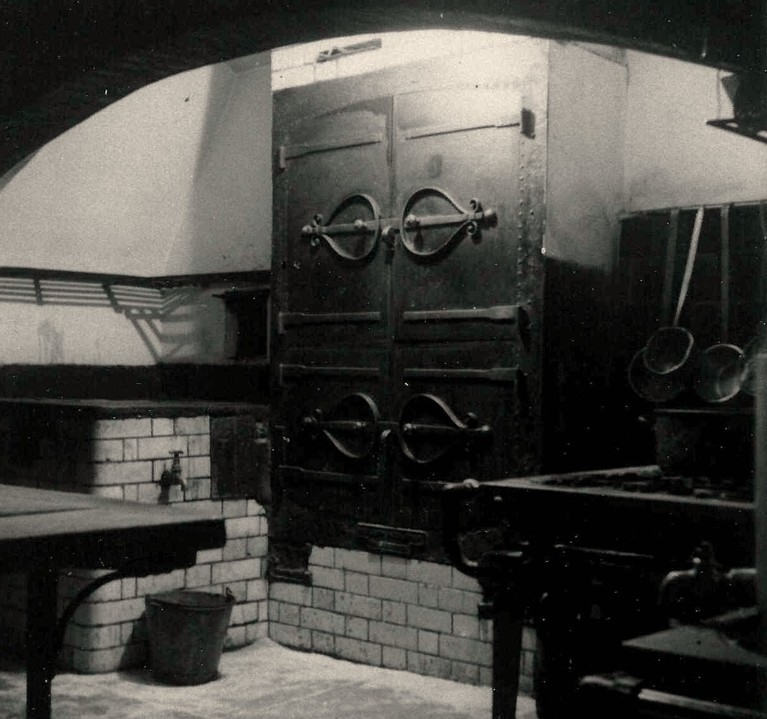

Image caption: A gloomy corner of the college kitchens, c.1950

It is, of course, customary for Emmanuel’s kitchens to close over Christmas and New Year, a policy accelerated in the early twentieth century by the steadily dwindling number of resident Fellows. Kitchen menu books of the 1920s and 30s show that no meals were served later than lunch on Christmas Eve, and that the kitchen staff did not return to work until early January.

This civilised arrangement came to an abrupt end upon the outbreak of the Second World War. North Court was taken over by the military for the duration, and as the servicemen’s meals were prepared by Emmanuel staff, the kitchens were obliged to stay open all year round. The Christmas newsletters sent to old members in 1942 and 1943 lament the consequences: ‘short rations, staff changes, no vacations…we stagger from domestic crisis to domestic crisis’. The principal strain fell on the catering manager, Mary Bolt, whose kitchen workforce consisted mainly of untrained young women who decamped to better-paid jobs at the first opportunity.

As far as members’ meals were concerned, the only concession made to the kitchen staff on Christmas Day was that they did not have to cook a hot dinner. The handful of resident students and Fellows living in college were certainly provided with an evening repast, but it consisted of a simple buffet of cold cuts, potato salad and dessert, laid out in the afternoon. There had been a decent mid-day meal, though; the 1940 Christmas Day luncheon, for instance, comprised roast chicken, sprouts and baked potatoes, followed by mince pies. The menu in the succeeding three years was identical, except that Christmas pudding replaced mince pies.

In 1944, when the war was nearing its final stages, the kitchens were able to close for four days over Christmas, and the following year the staff had eight days off. A note of festivity returned to the menu books, too, as the evening meal served on 21st December 1945 was described as ‘Xmas dinner’, a title not applied to anything served during the war. This did not, sadly, indicate a more sumptuous meal, as the bill of fare was virtually indistinguishable from the wartime Christmas Day lunches. The only touch of luxury was that the potatoes were roasted, not baked.

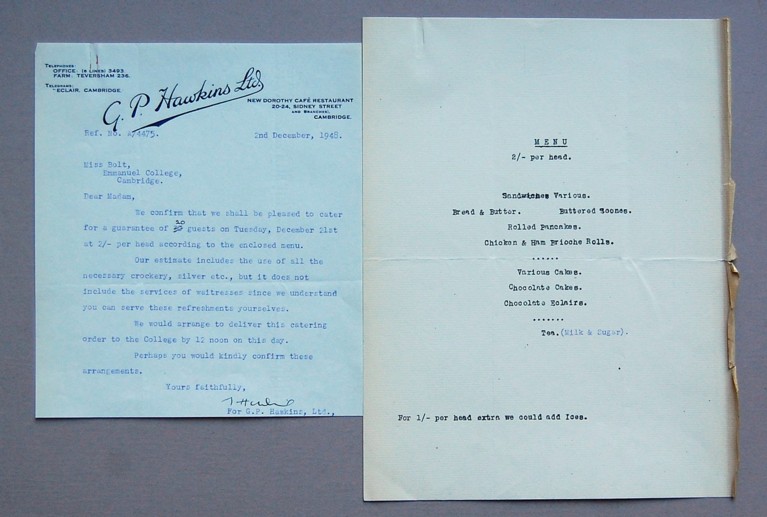

Image caption: Letter and menu for the college Christmas tea-party, 1948

The war might have been over (we have of course celebrated the 80th anniversary of its ending this year), but rationing continued, and it was several years before normal college hospitality was resumed. One of the earliest festive occasions was the dinner party hosted by Professor Ronald Norrish (one of Emmanuel’s three Nobel Prize winners) on Saturday 18th December 1948. Norrish was famed for his hospitality, and the guests stayed late into the night. Kitchen staff could leave, though, once they had cleared the dining table of all the food, plates and silverware. The porter on duty was instructed to check the gallery after everyone had gone, ‘and satisfy himself that no cigarette ends etc are left which could possibly cause a fire’. Different times! Three days later the college put on a Christmas tea party, presumably for the Fellows, but this did not involve extra work for kitchen staff, as the catering was provided by G P Hawkins of Sidney Street. The menu (shown above) sounds tasty enough, and although the chocolate eclairs may not have contained real cream, or indeed much chocolate, things were beginning to look up.

[The title of this piece derives from George Robert Sims’ famous Victorian poem, Christmas Day in the Workhouse, so beloved of the late Joe Grundy Esq of Ambridge. Sims’s melodramatic monologue has been much parodied, and at least two versions of Cookhouse are known, one of them featuring in the film Oh! What a Lovely War]

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

25 November 2025

S is for…Shuckburgh

Evelyn Shirley Shuckburgh, author of the first official history of Emmanuel College, is commemorated on a bronze plaque in the library. A fine piece by Ernest Gillick R.A., the sculpture does not, of course, convey the fact that its subject was tall, fair-haired and ruddy-cheeked. Shuckburgh was appointed to an Emmanuel fellowship after graduating 13th Classic in 1866. It was later recalled that he brought a ‘delightful freshness’ to the Fellows’ Parlour, although his blithe infringements of its more ‘absurd’ rules resulted in an ‘unprecedented total’ of fines. Upon his marriage to Frances Pullen, in 1874, Shuckburgh was obliged to resign his fellowship. He taught Classics for a decade at Eton, where his ‘tranquil kindliness’ endeared him to many pupils, but in 1884 he returned to Emmanuel, upon being appointed college Librarian. Shuckburgh was also a prolific translator and essayist, and was thus ideally fitted to write the Emmanuel volume in the University of Cambridge College Histories series. This book, published in 1904, is a highly readable, as well as useful, work of reference. Shuckburgh also wrote brief biographies of several Emmanuel worthies, and earned the enduring gratitude of researchers by translating, from the original Latin, William Dillingham’s invaluable memoir of Laurence Chaderton, the college’s first Master. In a letter written from Eton in April 1875 to a former colleague, Shuckburgh expressed a wish that it was the school holidays so that he ‘might lounge about for ever in this delicious weather’. In fact, he was an indefatigable worker, who when asked why he devoted so much leisure time to academic study, answered simply: ‘I enjoy it’. Overwork perhaps contributed to his sudden death in 1906, aged only 62. His friends remembered him as an ‘amiable, affectionate, charitable, large-hearted man’, with an immense enjoyment of life.

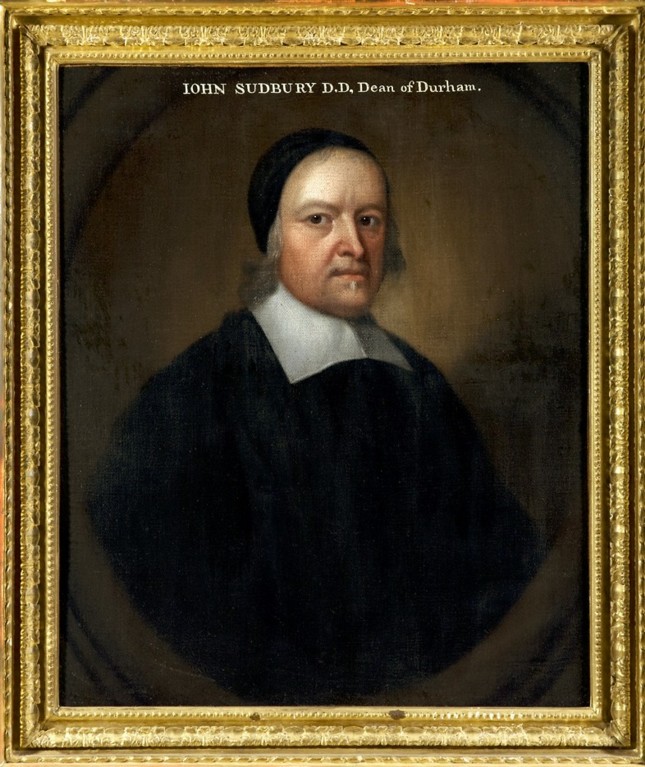

S is for…Sudbury Prize

A good many annual awards are now available to Emmanuel students, but for a long time only one was on offer: the Sudbury prize. The college’s early governors expected students to regard outstanding intellectual achievement as its own reward (with the contingent possibility of a fellowship, admittedly). After the disruptions of the Civil War and Commonwealth, however, it was felt by many, not least the new Master, William Sancroft, that the calibre of Emmanuel’s students needed raising. John Sudbury, admitted to Emmanuel in 1620, shared this opinion. A churchman and Royalist, Sudbury was deprived of his clerical living in 1642, but after the Restoration was appointed Dean of Durham. In 1667, he informed Sancroft that following their recent discussion, he would be giving the college £500 to fund, amongst other things, an annual student prize. Sudbury hoped this would be ‘an incentive to young schollers to study to deserve, partly for the advantage, which is but small, and partly for the honour of being reputed the most worthy of their year, and therefore I intend it shall be bestowed upon no other consideration but that of merit for learning and piety’. The prize was to be a piece of silverware worth £6, awarded to the BA commencer judged by the Master and senior Fellows to be the most deserving. The prizes could take any form (many recipients chose drinking vessels), but all were to bear the same Latin inscription, commemorating Sudbury, that Sancroft himself had composed. The award was later augmented by other benefactors and is now called the Sudbury-Hardyman Prize. It is currently reserved for students excelling in academic subjects for which no other named prize exists. Historic ‘Sudbury’ silverware occasionally comes up for sale, and several pieces have been acquired for the college, thanks to the generosity of an old member.

24 November 2025

As the final leaves fall and the days draw in, the gardens at Emmanuel College move into their quietest - but by no means least important - season. Winter preparation work is well underway and these late-autumn tasks help shape the displays and habitats that will flourish when spring returns.

Camassia Bulb Planting in North Court Meadows

This year’s major highlight has been the planting of Camassia bulbs in the North Court meadows. These elegant, starry-flowered perennials are perfectly suited to naturalising in grass and we’re introducing them to mingle with the existing wildflower mix. Over time, the Camassias will create soft drifts of blue and cream in late spring, rising above the meadow foliage and adding both height and colour to the early-season tapestry. Planting now ensures they receive the necessary winter chill to break dormancy and settle in for a long life among the meadow’s native species.

Tending the Meadow for Winter

The meadows themselves have been cut back and raked to reduce fertility - an important step in supporting the more delicate wildflowers that thrive in leaner soils. With the new bulbs tucked safely into the turf, the meadow enters a resting phase, ready to surge back with fresh energy in April and May.

Annual Cutting Back Around the Pond

Another key winter job has been the annual cutting back of the vegetation around the pond. This maintenance helps keep the waterbody healthy and prevents excess organic matter from accumulating and reducing oxygen levels. By clearing reeds, spent marginal plants and overhanging growth, we preserve open water, improve light levels and maintain a variety of habitats for amphibians, aquatic insects and overwintering birds. It’s a careful balance - enough clearing to protect the pond’s ecology, but always leaving sections untouched to provide shelter and continuity for wildlife.

Looking Ahead

Though the gardens may appear still in these colder months, the groundwork laid now prepares the landscape for a vibrant spring. We look forward to seeing the new Camassia begin their first tentative emergence next year and to welcoming the wildlife that relies on Emmanuel’s carefully tended habitats throughout the seasons.

Stay warm and we’ll share more updates as the turn of the year brings fresh signs of life back into the gardens.

Best wishes

Brendon Sims (Head Gardener)

29 October 2025

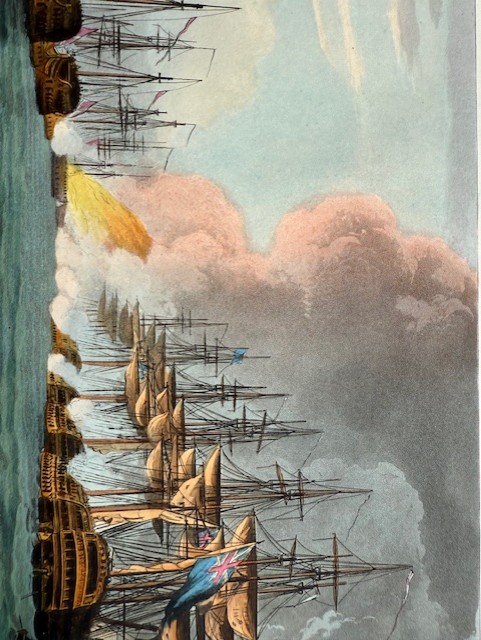

'The Battle of Trafalgar', in J. Jenkins, 'Naval Achievements of Great Britain' (1816-1817)

How did you spend Oak Apple Day this year? (It was 29 May). And how did you mark Trafalgar Day? (It was last week, 21 October, in case you missed it). These are just some of the national anniversaries once observed and now generally forgotten.

Oak Apple Day commemorated the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 on what happened to be Charles II’s thirtieth birthday and featured the wearing of sprigs of oak leaves and oak apples, in memory of how Charles hid in an oak tree after the Battle of Worcester in 1651. During the nineteenth century, and at the centenary in 1905, the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar was solemnly commemorated as a moment of national salvation, perhaps comparable to how the Battle of Britain in 1940 is now remembered. But widespread observance of Trafalgar Day faded away after two world wars brought more urgent and recent reasons for commemoration, also observed at this autumnal season of the year.

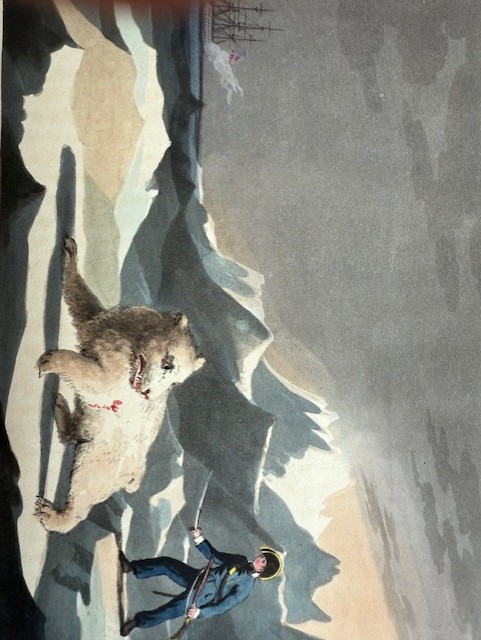

The construction of Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) as a national hero is recorded in some of the illustrated books from his times in Emmanuel’s collections. Blagdon’s Graphic History (1806), a reverent commemoration of Nelson’s life, duly records the youthful hero’s early bravado during a naval voyage into polar waters.

F. W. Blagdon, 'Orme's Graphic History of Horatio Nelson' (1806)

Missing and presumed lost, our hero has actually been hunting a polar bear across the ice. His gun having become unworkable due to ice, he finishes the bear off with a blade. Reprimanded, he replies that he wanted the bearskin for his father.

Nelson’s naval victories such as the Battle of Copenhagen (1801) and the Battle of the Nile (1798) were decisive turning points, recorded in Jenkins’s Naval Achievements of Great Britain (1816-1817).

Jenkins, 'The Battle of Copenhagen'

Jenkins, 'The Battle of Copenhagen'

Jenkins, 'The Battle of the Nile'

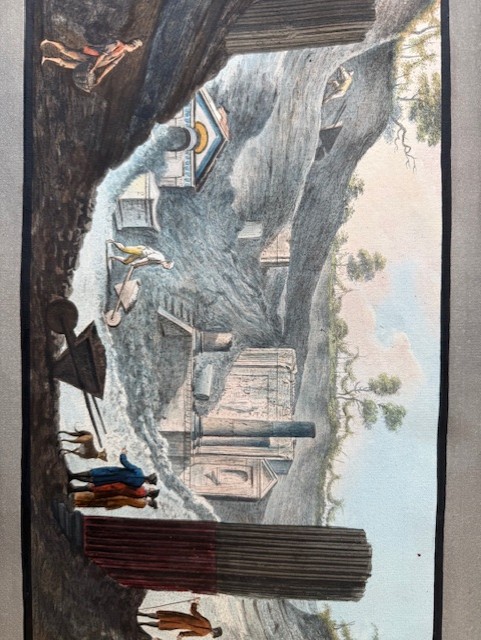

Yet during his lifetime in the public eye, Nelson the naval commander was also known for his unorthodox private life. Sir William Hamilton (1731-1803), the widower British Ambassador in Naples, had become smitten with Emma Lyon, an artist’s model of humble origins who was 34 years his junior, and had made her his second wife. Hamilton was an avid collector of antiquities and interested in the excavations at Pompei.

Excavations at Pompei, in Sir William Hamilton, 'Campi Phlegraei' (1776)

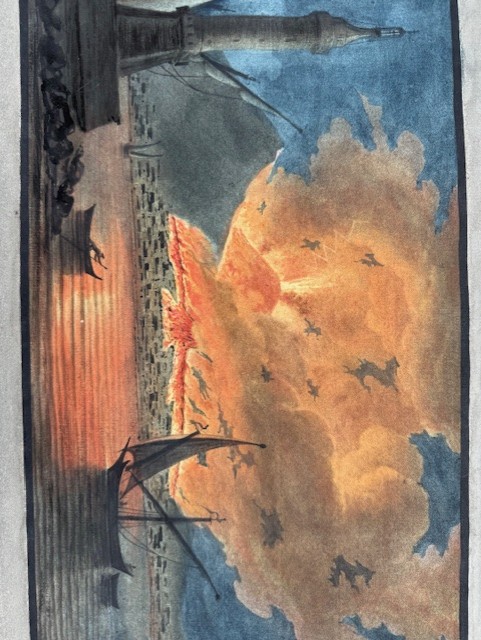

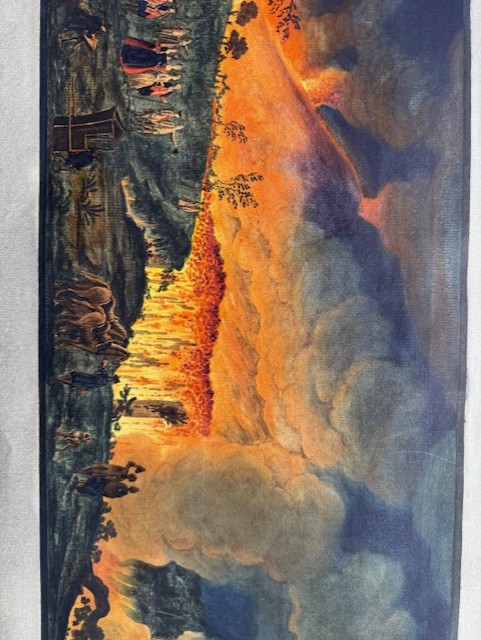

Hamilton was also a serious early investigator of volcanic eruptions. His Campi Phlegraei (1776) studies the eruptions of Vesuvius during his long ambassadorship, with 50 hand-coloured gouache illustrations by Pietro Fabris, including study of the changing nature of the volcano summit.

'Campi Phlegraei'

'Campi Phlegraei'

Also depicted are flaming lava flows spreading dramatically across cultivated countryside, while another striking image shows Hamilton conducting the King and Queen of the Two Sicilies to observe an eruption at close quarters.

'Campi Phlegraei'

'Campi Phlegraei'

Nelson’s affair with Lady Hamilton became a contemporary scandal, less because it began than because it settled into an established threesome for the rest of Hamilton’s life. With characteristic savagery, the caricaturist James Gillray satirizes Lady Hamilton as a by now distinctly obese Dido lamenting the departure to sea of her Aeneas. British naval vessels are seen on the horizon and Hamilton is just visible, sleeping squashed beside her. His books on antique subjects are scattered about, along with a broken statue of Priapus.

'Dido's Despair' in James Gillray, 'The Caricatures' (c.1800-1806)

When Hamilton was recalled to London, the ‘throuple’ travelled back as a threesome, with Emma duly giving birth to Nelson’s child. Both Emma and Nelson were present at Hamilton’s deathbed, and Hamilton bequeathed Nelson his portrait of Emma by Elizabeth Vigée le Brun.

Eternal fame would be secure for the brilliant naval strategist who was to die on his aptly-named ship Victory in the very moment of his triumph over the French and Spanish fleets off Cape Trafalgar, securing Britain’s command of the seas for the rest of the Napoleonic Wars and putting paid to any prospect of a French invasion. Nelson’s strategy was to break the enemy line of ships by sailing at right angles to it. Despite being outnumbered in ships and men, Nelson’s victory was a rout, although the battle was severe.

'Breaking the Line at Trafalgar', in Jenkins, 'Naval Achievements'

'The Battle of Trafalgar' in Jenkins, 'Naval Achievements'

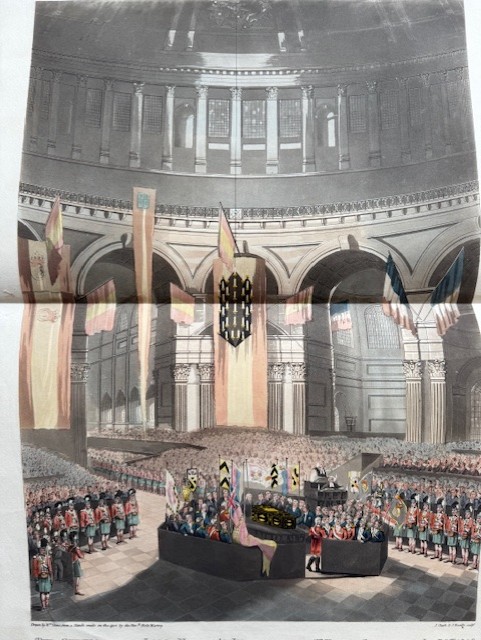

In death, Nelson was accorded an unparalleled state funeral as a national hero, only repeated since on the same scale for Wellington and Churchill. Blagdon’s Graphic History recalls its majesty for a contemporary readership. There is the voyage along the Thames, also part of Churchill’s funeral, and the extraordinary vehicle on which the hero’s coffin was conveyed – something comparable was designed for Wellington.

'Nelson's Funeral Procession by water from Greenwich Hospital to Whitehall', in Blagdon, 'Graphic History'

Nelson's Funeral Carriage nearing St Paul's, in Blagdon, 'Graphic History'

Finally there were the obsequies beneath the dome of St Paul’s amid a vast congregation, and the toast repeated on each Trafalgar Day since, which always includes the words ‘To the Immortal Memory … ’.

Funeral and Interment in St Paul's, in Blagdon, 'Graphic History'

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books

29 October 2025

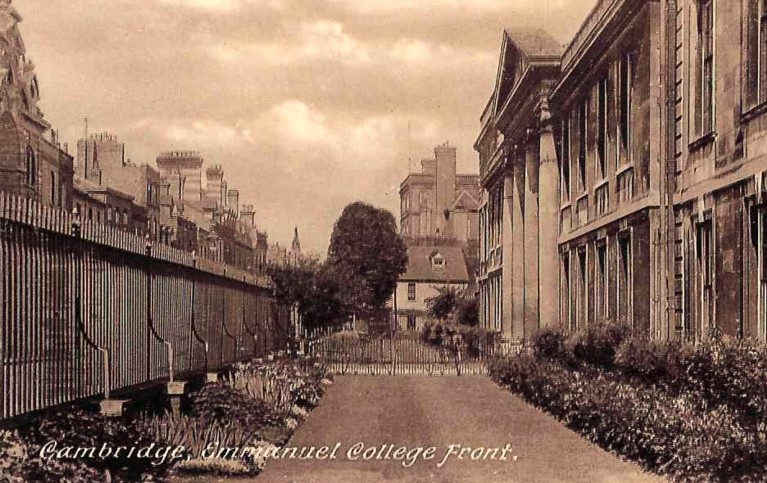

R is for … Railings

When Emmanuel’s western frontage, the Essex Building, was erected in the 1770s, it was deliberately set back from the busy highway of St Andrew’s Street. A low brick wall with stone coping, topped by high iron railings, gave a further measure of protection. They can be seen in this 1931 postcard, recently donated by an old member of Emmanuel. The railings fronting the college today are not the Georgian originals. In the summer of 1940, in response to the wartime appeal, the college sacrificed most of its railings, including the stretch along St Andrew’s Street. The Master, ‘Timmy’ Hele, thought this made ‘an immense improvement’ to the college’s appearance, telling a correspondent that ‘our forebears did like iron, and their love of iron has put quite a nice little store at the disposal of the government’. Would that it had! After the war, the college bursar was told on the Q.T. that the railings had got no further than a scrap yard near Wisbech. With its protective ironwork gone, the college frontage was very exposed, although shrubs and saplings planted in the slips provided some screening. When Lord St John of Fawsley became Master of Emmanuel in the early 1990s, he was keen to restore the ‘handsome’ railings that had formerly ‘set off the Essex façade’ and afforded ‘much needed protection to the gardens behind’. A generous benefactor offered to fund the project. Planning regulations required that the new railings replicate the originals as closely as possible, so old engravings and photographs were scrutinised. The new ironwork was installed in 1997, to general approval. The trees planted in the slips after the war eventually succumbed to honey fungus and were felled in 2008, but this has allowed the elegance of the railings to be fully appreciated.

R is for … Regicides

The term ‘Regicide’, in respect of King Charles I, refers to the 59 signatories to his death warrant, and selected others who had played an active role in his arraignment and execution. An eighteenth century engraving in college’s print collection (pictured) shows the King’s trial. Emmanuel College, to its credit or otherwise, supplied three of the six Cambridge University regicides. These individuals, all of whom signed the death warrant, were William Purefoy (admitted 1598), Augustine Garland (1618) and Thomas Scot (1619). Purefoy, although a Calvinist, never took holy orders, preferring a career in politics and the army. In August 1659 he was ordered to suppress Sir George Booth’s royalist uprising, despite the fact that, as fellow regicide Edmund Ludlow put it, he had ‘one foot in the grave’. Colonel Purefoy did in fact die the following month, thus escaping retribution after the Restoration of Charles II. Following the monarch’s return in 1660, all the surviving regicides who could be tracked down were apprehended and tried for treason, including Thomas Scot, who had fled to Brussels. Augustine Garland was also arrested, but claimed that he had only signed the death warrant under acute pressure and fearing his ‘own destruction’. This plea was convincing enough to save his life, but he was sentenced to exile in Tangier. Scot was cut from a different cloth and remained defiantly unrepentant to the end. For him there could be no mercy, and he was hanged, drawn and quartered in October 1660. Garland and Scot may have encountered a familiar face during their imprisonment, as one of Commissioners appointed to try the regicides was the Royalist judge, Sir Christopher Turnor, who had been admitted to Emmanuel in 1623. Some years later, Turnor gave his old college £10 towards the building costs of Wren’s chapel.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

29 October 2025

As the days grow shorter and the air takes on a crispness that signals the turn of the season, Emmanuel College’s gardens and trees transform into a vibrant tapestry of golds, russets, and scarlets. Autumn is one of the most beautiful times to walk through the College grounds – the reflections in the ponds shimmer with colour, and every pathway seems to glow beneath canopies of changing leaves.

Among the college’s most striking trees at this time of year are the liquidambar by the Paddock, which turn deep crimson and purple, and the golden ginkgo that brightens the Fellows' Garden with fan-shaped leaves. The lime tree on the gravel drive shifts gradually from a rich green to a mellow yellow, while the parrotia in Chapman’s Garden put on a spectacular display of vibrant yellow.

But what causes this annual spectacle? The answer lies in the chemistry of the leaves themselves. During spring and summer, chlorophyll – the green pigment essential for photosynthesis – dominates, capturing sunlight and converting it into the energy that fuels the tree’s growth. As autumn approaches and daylight diminishes, the trees prepare for winter dormancy. Chlorophyll production slows and eventually stops, revealing other pigments that were hidden beneath the green.

Carotenoids, responsible for the yellows and oranges we see in species such as birch and beech, remain in the leaves after chlorophyll fades. Anthocyanins, which produce reds and purples, are created anew in some trees as sugars become trapped in the leaves during the cool nights and bright days of early autumn. The balance of these pigments – combined with the particular weather patterns of each year – determines the intensity and range of autumn colour we enjoy.

At Emmanuel, the gardeners take great care to nurture this seasonal richness. Trees are selected and tended, not only for their health and form, but also for their contribution to the beauty of the College throughout the year. In autumn, this careful stewardship rewards all who pass through the courts and gardens with a reminder of the cycles of nature and the quiet splendour that accompanies change.

Whether viewed from a study window, on a walk between lectures, or during a reflective moment by the pond, the autumn colours at Emmanuel are a source of delight and inspiration – a vivid celebration of the turning year within the heart of Cambridge.

This autumn colour, however, may be short-lived due to the heavy rain and extreme winds. The team are busy chasing the leaves, often clearing an area, only to turn their backs to find the tree has shed more leaves.

Brendon Sims, Head Gardener

2 October 2025

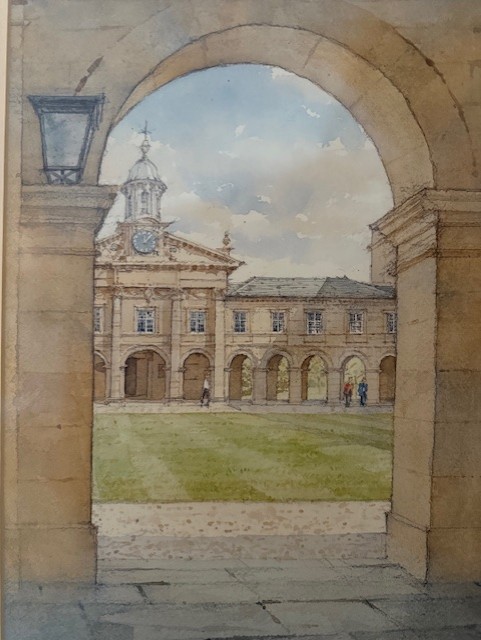

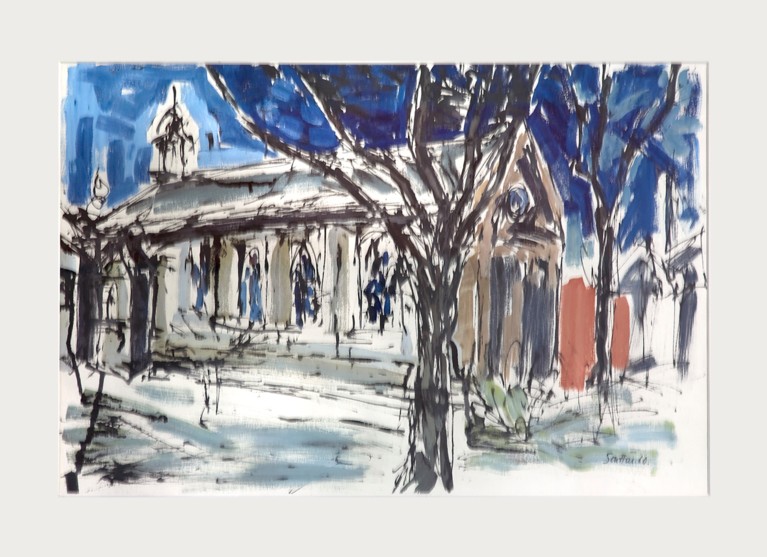

Although there are prints of Emmanuel, as of other Oxbridge colleges, from the eighteenth century onwards, the College’s collections contain rather few oil paintings or watercolours depicting Emmanuel before the twentieth century. Modern paintings and prints of Emmanuel – a serendipitous range of items – can offer a snapshot of tastes and trends across the past century. The watercolour above, perhaps dating from the 1930s is a valuable witness, recording Emmanuel’s unusualness among Cambridge colleges in having a front garden, once with the lawns and colourful bedding shown in the watercolour. Extreme right, along with the spire of Our Lady and the English Martyrs, are the railings, removed during World War Two, and replaced in the 1990s.

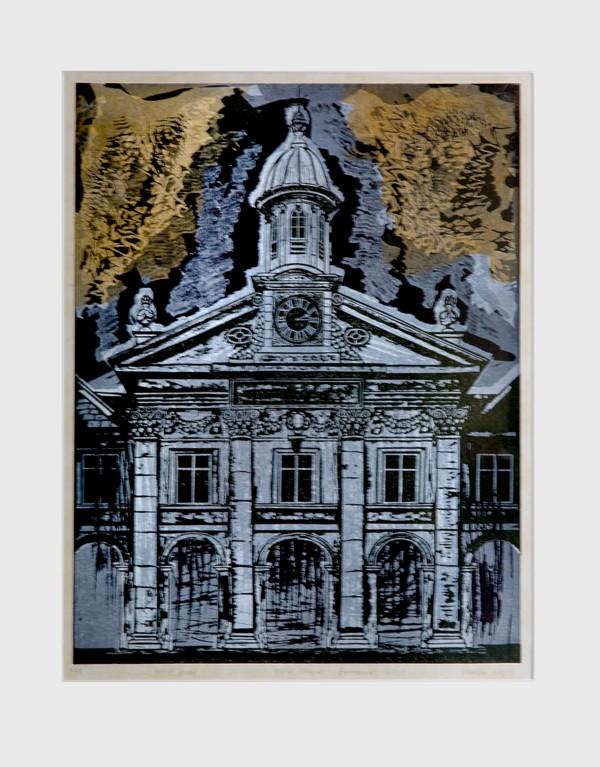

Of twentieth-century images of Emmanuel, the majority focus on the front of the Wren Chapel itself, or as seen across Front Court. From 1965-1966 there is a striking print of the Chapel Front by Walter Hoyle (1922-2000):

Painter, illustrator and printmaker, Hoyle was a member of the artists’ group based at Great Bardfield in Essex and later taught printmaking in Cambridge.

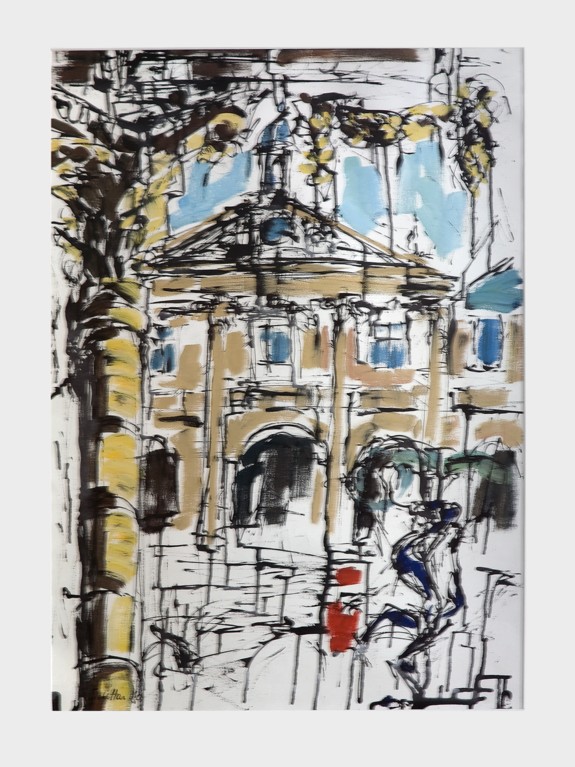

Another vision of the Chapel Front (c.1960; oil on paper) was commissioned by the Emmanuel Art Society from the Irish abstract and landscape artist Camille Souter (1929-2023):

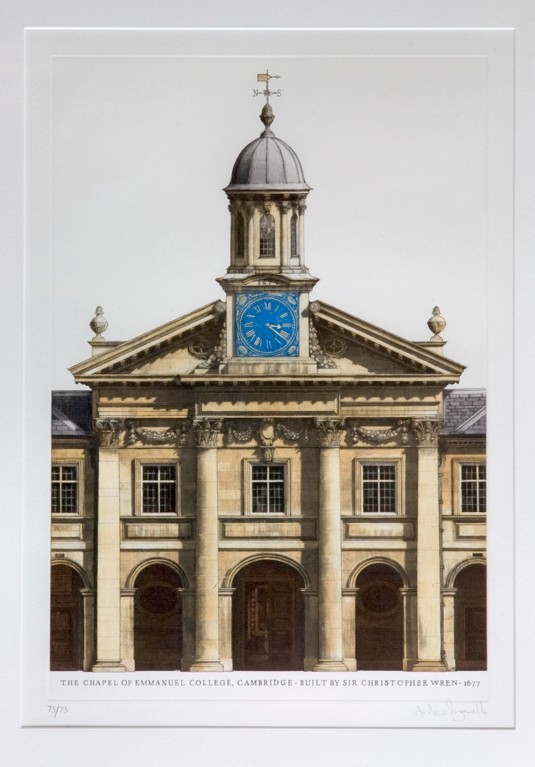

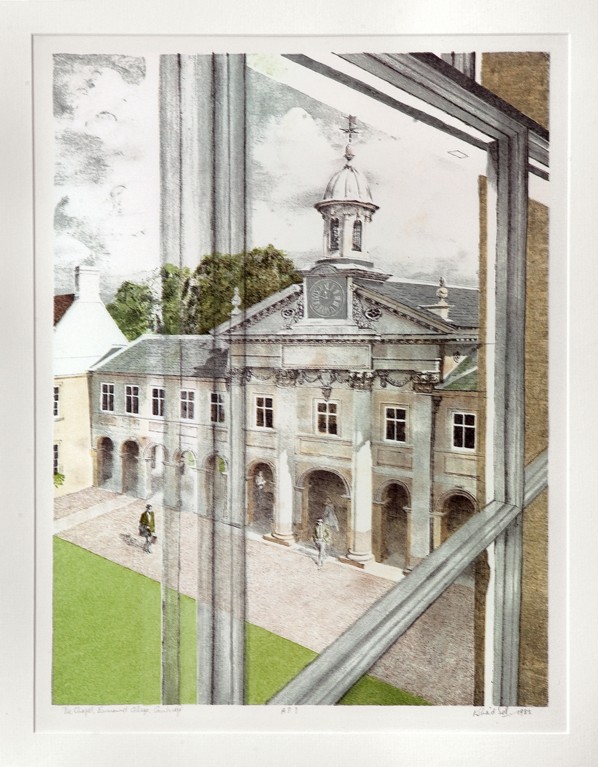

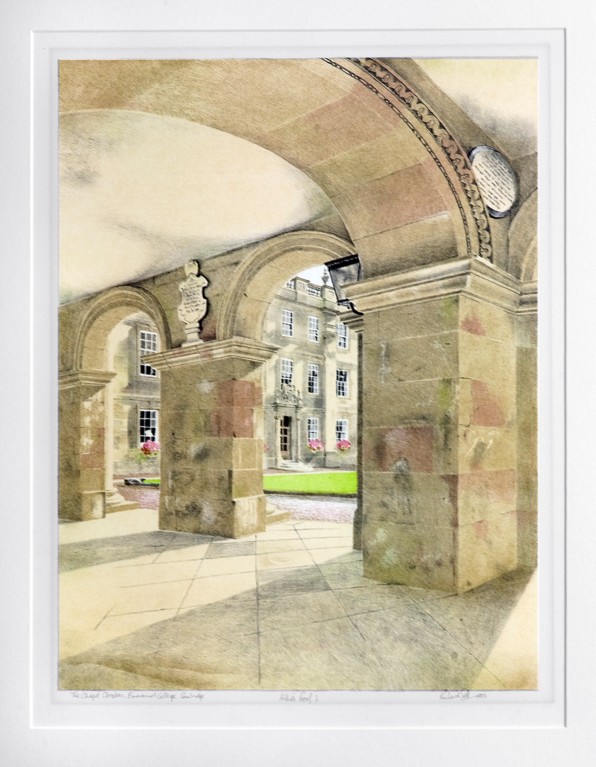

The artist and printmaker Andrew Ingamells (b. 1956), who specializes in architectural subjects, has produced a modern take on traditional prints of the Chapel Front, just as he has been commissioned to reinvent David Loggan’s late-seventeenth bird’s eye views of many Oxbridge colleges, including Emmanuel:

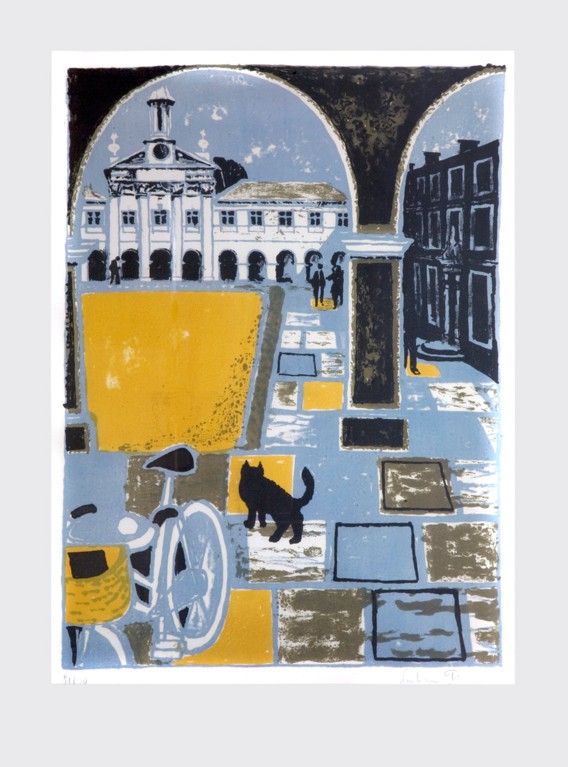

Among views of the Chapel Front across Front Court are the lithographs in various colour ways (1959-1962) by Julian Trevelyan (1910-1988), a significant figure in developing modern print technique. A purposeful black cat, near the centre of the composition, seems to be surveying the scene as much as any human viewer:

A more representational approach to a similar prospect is taken by the watercolourist Dennis Roxby Bott (b. 1948), who often takes architecture and the built environment as his focus, in this print based on a watercolour:

Hugh Casson (1910-1999), architect of the Raised Faculty Building on the Sidgwick Avenue site, published the illustrated books Casson’s Oxford and Casson’s Cambridge, with associated series of limited edition prints, among which is his view of the Chapel Front across Front Court:

In one of his three prints commissioned by the College for the 1984 Quatercentenary, the East Anglian artist and printmaker Richard Sell sought out an original perspective, framing the Chapel Front as seen through a window in the Westmorland Building:

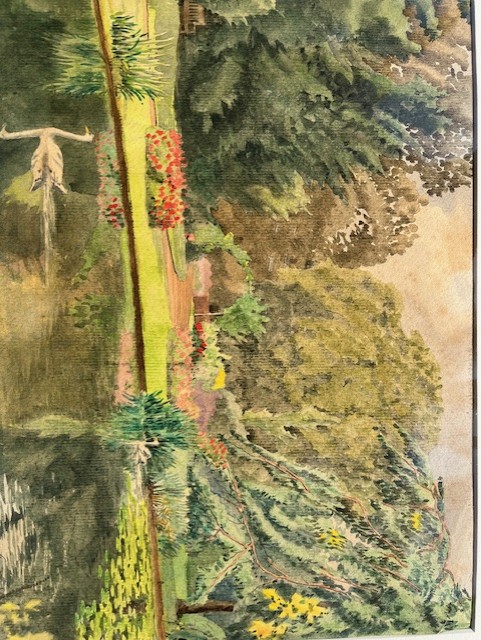

Painted images of Emmanuel outside Front Court are less frequent. F. A. Molony painted several watercolours of the Paddock, including one looking across the Pond (with resident swan) to the Fellows’ Garden and plane tree:

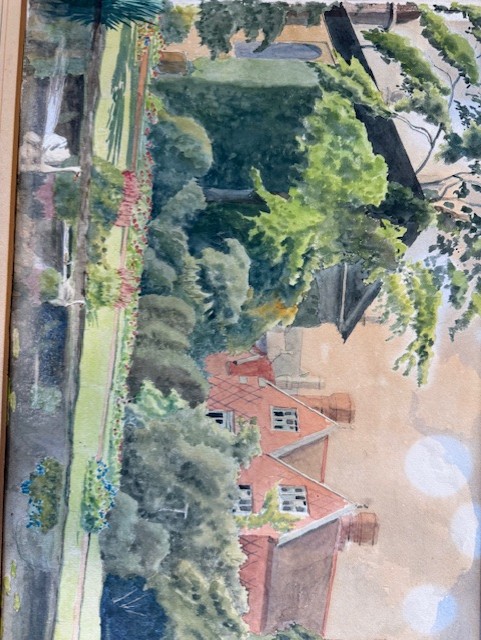

Molony also painted the view of the Chapel across the Pond (two swans, plus cygnet), showing the Victorian Master’s Lodge, which would be demolished and replaced in the 1960s. (And no, that’s not three UFOs landing in the Paddock but damage to the painting):

Molony (d. 1944) was a Victorian soldier who, after serving in Sudan and the Boer War, took up watercolour painting and in later life settled in Cambridge. The compositions of some of his paintings of Cambridge colleges may be based on contemporary postcards.

At least that cannot be said of Camille Souter’s painting of the Chapel, also from the Paddock:

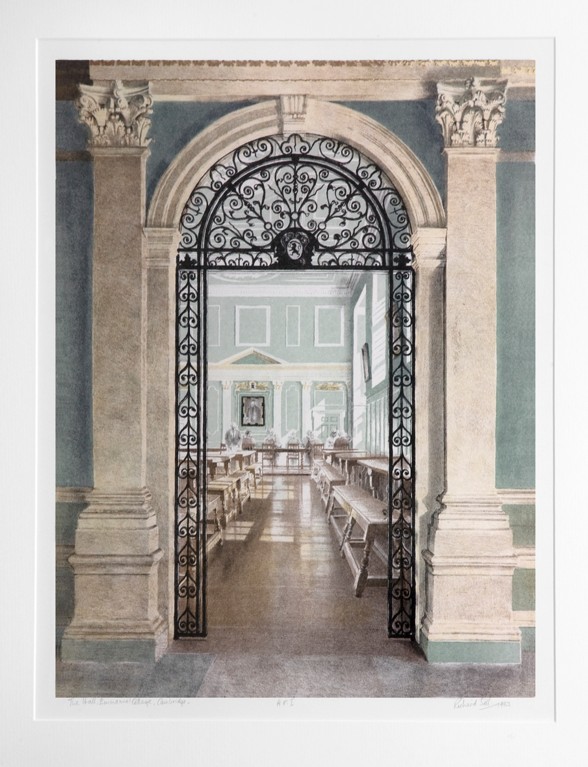

Richard Sell’s other prints highlight less familiar angles of Emmanuel, such as the Chapel Cloisters, or the doorways into the Hall, with their fine iron gates of 1762 (as captured in Sell's preliminary drawing and in the finished print):

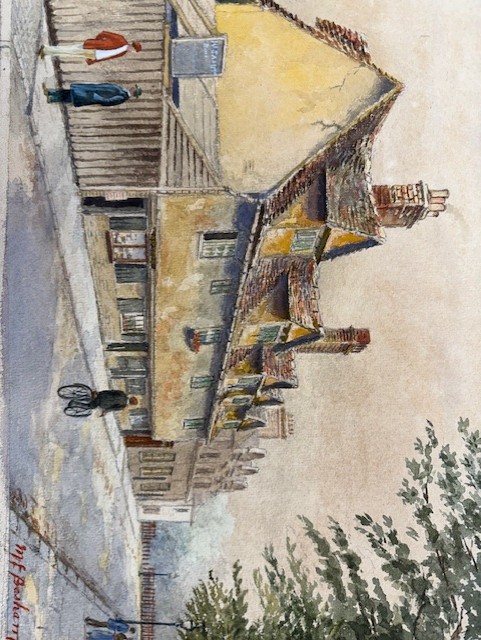

By contrast, images of streetscapes near Emmanuel – such as an oil painting of part of St Andrew’s Street between Emmanuel and Christ’s, or a watercolour of the quaint cottages that once stood where North Court now faces the street (picked up on Ebay in 2025!) – are a reminder that while the town around them changes the fabric of Cambridge colleges tends to remain, with adaptations, much the same:

Barry Windeatt (Keeper of Rare Books)

2 October 2025

Q is for… Quatercentenary, Queen Elizabeth II & Quercus robur

A college event combining three Qs may sound unlikely, but such a confluence occurred on 16 May 1984. On that memorable occasion, Queen Elizabeth II, accompanied by Prince Philip, then Chancellor of Cambridge University, visited Emmanuel to mark the 400th anniversary, or quatercentenary, of its founding. As well as touring the older parts of the college, Queen Elizabeth planted an English oak (Quercus robur), that has since grown into what might fittingly be described as a majestic tree. A member of the royal entourage confided to one of the college Fellows that the Queen was unwell, and that anyone else would have cancelled the engagement. The sovereign nevertheless snapped to attention when shown one of the treasures of Emmanuel’s library, a prayer book almost certainly once owned by Arthur, Prince of Wales, Henry VIII’s short-lived older brother. Confronted with its copious Tudor heraldic illumination, including the ‘three feathers’ badge of the princes of Wales, her late Majesty immediately asked: ‘How did this get here?’ (it must have been a gift from the college’s Founder, Sir Walter Mildmay, but how he acquired it is unknown). Queen Elizabeth’s visit was the highlight of Emmanuel’s quatercentenary celebrations, but there were many other festivities, including a garden party. A special exhibition was put on at the Fitzwilliam Museum, displaying the most prized items from Emmanuel’s collections of archives, manuscripts, books, plate and pictures. Selecting a definitive date for the foundation of our college is impossible. For one thing, the process involved a series of preliminary property transfers, commencing in 1583. For another, there were not one, but two, principal foundation instruments. These were the charters granted by Elizabeth I and Sir Walter Mildmay, dated 11 January and 25 May 1584, respectively. The college was not ready to admit students, though, until November of that year.

Q is for…Query Club

Since the formation of the Emmanuel Boat Club in 1827, a good many student clubs and societies have flourished here. Some are still going strong, while others dissolved after a decent innings. Quite a number lasted only a few years, leaving little or no documentation. They included the Nightwatchmen (purpose uncertain), the Sauceboat Club (fine dining), the Hort Society (Catholicism), the Scramblers (breakfast club) and the Lay Brothers (evensong, mead-drinking and picnics in punts!). A short-lived Edwardian society was the Query Club, that existed for only two years and soon passed from collegiate memory. Fortunately, its solitary minute book came to light decades later. The club was established in February 1910, its object being ‘the discussion of social, political, & religious problems’. Presumably, the adversarial format of the college Debating Society did not appeal to the Query Club’s members. They were an enthusiastic bunch, whose discussions were impressively wide-ranging and covered many topics that are still relevant today. Predictably, choosing the design of the termly meeting cards generated a prolonged discussion in itself, but eventually members settled on the logo shown above. Fans of the ‘Three Investigators’ juvenile detective books will be amused to know that a motif comprising three question marks in a row was always printed inside the cards. In common with so many of the college’s short-lived student societies, the Query Club did not survive the departure from Emmanuel of its founding members. Joshua Burn, one of the principal instigators, took the club’s minute book with him when he graduated in 1912, carefully preserving it until his death in 1981. This slim volume shows that the Query Club provided its members with, above all else, a huge amount of fun – and that was more than enough to justify its brief existence.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

1 October 2025

September in the Emmanuel Gardens – A New Term Begins

As the long days of summer gently give way to the mellow light of early autumn, we’re delighted to welcome students - both new and returning - back to Emmanuel College. The gardens, having quietly flourished over the break, are now ready to be rediscovered and enjoyed once again.

September is a moment of quiet transition in the garden. The borders are still rich with late-summer colour: rudbeckias, sedums, and Michaelmas daisies bring warmth and vibrancy, echoing the soft gold of turning leaves. The ancient trees along the Paddock are just beginning to show the first hints of autumnal colour, a gentle reminder of the seasonal shift. As October descends on us, the nights start getting cooler and the leaves start gently fluttering down. A sign of things to come.

Over the summer, the Garden Team has been busy with maintenance and quiet improvements. You may notice refreshed planting in some of the perennial beds, as well as continued efforts to enhance biodiversity across the College grounds. Our wildflower areas have been particularly successful this year, providing late nectar for bees and other pollinators. We have been busy harvesting the seeds from hay bales donated to us from King's College meadows, as well as harvesting them ourselves from our own meadows. We shall sow these wildflower seeds back into our meadows soon. Certain seeds need a period of cold weather to help with germination. Sowing at this time of year should ensure that.

For new students, we warmly encourage you to explore the gardens as a place of rest, reflection, and inspiration. Whether it's reading by the Pond, taking a walk through Chapman’s Garden, or simply finding a quiet bench, these green spaces are here for you.

The garden department would like to welcome new students and returning community garden growers, back to our community garden this year. Although the students were no longer here, the produce was shared around the staff and visitors, with donations being placed outside the Porter’s Lodge. We did sow some pumpkins and squashes, and they should be ripening just as the students return.

As we move into a new academic year, the gardens will continue to evolve with the season - but their role remains the same: to offer beauty, peace, and a deep breath of nature amid the busy rhythm of college life.

best wishes,

Brendon Sims (Head Gardener)

3 September 2025

.jpg)

This edition of the garden news has been hard to write as my emotions are a bit raw from the last few days. Unfortunately, on Saturday 30th August, I was notified by the Porter’s Lodge that a large branch had come down on a tree in Chapman’s Garden. I hate receiving calls at home at the weekend because this is nearly always the reason.

I was sent some pictures of the large branch, still attached to the tree, by the Porters. The original phone call had told me that the Tulip tree had split in half, and my stomach just sank at the thought of this monster tree and its location within the college. I was relieved to see from the pictures that it was not the Tulip tree with the failed limb. The tree was in fact the Sweet Gum Tree (Liquidambar styraciflua).

Professor Robert Macfarlane had been in Chapman’s Garden that day and heard the creaking of the branch. Robert managed to capture the moment the branch failed on video. This is something that was very helpful to see in real time. It is rare to capture these moments. However interesting capturing this moment was, I had to remind Robert that maybe it was not best idea to stand close to a tree that is failing. We shared a joke about the ironic thought of Robert dying in the landscape at Emmanuel College, but in all seriousness, please keep safe.

The sad thing about this event was that there was absolutely no warning of this branch failing. The garden team (and I) had been working in Chapman’s Garden all day just the day before. Whenever I am in the gardens, I visually check the trees. There was no sign of damage whatsoever.

The Friday evening saw heavy rainfall, something that at the time I was very grateful for given the months and months of dry hot weather. This could well have been a major contributary factor of the failure of the branch. After a full weekend of consulting with tree surgeons (and consultants), it was felt that the probable cause of the failure was SBD. Sudden Branch Drop Syndrome, also known as Summer Branch Drop (SBD), is the phenomenon of large, mature tree branches failing and falling without warning, often in calm weather, after a hot, dry spell followed by heavy rain. While the precise cause is not fully understood, it’s thought to involve a combination of factors like added weight from foliage or rain, internal water pressure, heat stress, and unseen structural weakness or decay within the branch. There may have been a weakening of the branch due to bark inclusion although that was not visible.

Our most recent professional tree survey had deemed the tree to be in good health but given the recent weather extremes, we can only assume that this was a contributary factor in the branch failing.

Unfortunately, on closer inspection from the tree surgeons, it was clear that the damage caused from the wound left on the tree, compromised its safety. The wound was so significant that the tree had become top heavy and that the wound had been at a pivot point for the tree. Even in the slight wind, the risk was significant enough to condemn the tree, given its size and location.

The college protocols worked well with securing the area for safety and the tree surgery team did a fantastic job removing the tree given its tricky location and limited access. This was a complex job and tackled with great care with health and safety at its foremost concern.

Unfortunately, as a gardener, you become emotionally attached to things such as trees. Some people will not understand the reaction but working within a landscape, seeing and dealing with the trees daily over a period, it’s hard not to feel a connection. The Liquidambar tree in Chapman’s was large and magnificent. The Sweet Gum tree as it is commonly known, produces brilliant autumn foliage colours and is a tree that dominates the landscape at this time of year. The colours of the leaves change from the green pigments, all the way through to reds, with every colour in between. This is a tree I would regularly do plant identifications with, passing on knowledge to my staff and to students. It was something that I would look forward to every Autumn. It punctuated the seasons for me and many others. It was with a heavy heart that I had to say goodbye this week. The tree itself was not that old. The tree rings suggested 48 years old, so it’s been around for half a century. Not long enough. If the wound had been in a different place, the tree might have been saved. The health and safety of others will always decide its outcome.

RIP friend.

Best wishes

Brendon Sims (Head Gardener)

2 September 2025

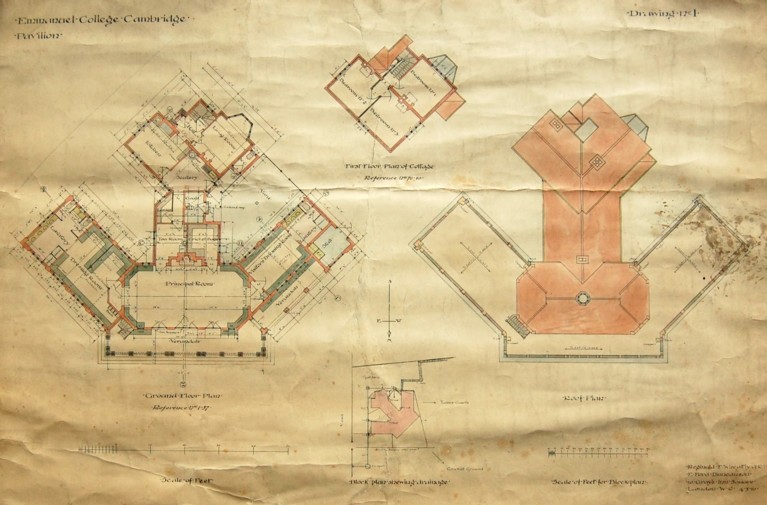

P is for…Pavilion

In Michaelmas Term 1907, after years of sharing a sportsground with other colleges, Emmanuel College bought a plot of land on Wilberforce Road and set about improving the turf. The college launched an appeal in 1908, informing members that the ‘New ground’ would provide room for cricket, football, hockey and tennis. It was hoped that the appeal would raise £1500, enough to cover the anticipated costs of constructing a sports pavilion and groundsman’s cottage in a corner of the site. The college commissioned architects Wheatley and Duncanson, of Grays Inn, to produce designs. They proposed a central reception room with flat-roofed receding wings, one of which incorporated a stable for the pony needed to pull the roller and mower. The Bursar, James Peace, particularly liked the cut-off corners of the principal room, as they ‘gave a character which it otherwise might not have’. To the rear of the communal area, utility rooms led to the groundsman’s cottage, the footprint of which echoed the angles of the wings. The appeal circular had stressed that the pavilion’s design would ‘avoid unnecessary ornament and elaboration’, so it came as a nasty shock when all the builders’ tenders were in the region of £2500. The Bursar’s immediate reaction was to instruct the architects to omit one of the wings completely, although he acknowledged that this would ‘destroy the symmetry’ of the building. In the event, this unappealing solution was avoided, thanks to the implementation of some cost-cutting modifications. The pavilion was ready for use by Michaelmas Term 1910, and despite the economies made in its construction, it is a most attractive example of Edwardian sports architecture. Sadly, the open viewing gallery that formerly ran above the verandah and wings had to be removed some years ago.

P is for…Pulpit

Pulpits are not a common feature of Cambridge college chapels, but Emmanuel’s early Fathers, being Puritans, placed a strong emphasis on preaching. The original chapel was therefore furnished with a pulpit, along with a ladder and a stand for an ‘howerglasse’ (the sermons delivered by Emmanuel’s first Master, Laurence Chaderton, were famously lengthy). A pulpit ‘Cushion’ is mentioned in a chapel inventory of April 1637. This was presumably the opulent cushion lately purchased from ‘Mr May the Upholster at London’, for the whopping sum of three guineas. When Emmanuel’s new chapel was consecrated in 1677, the unfashionable Elizabethan pulpit was surplus to requirements, but it soon found an appropriate new home. An entry in the church register of Trumpington, near Cambridge, notes that parishioner Thomas Allen, who died in 1692, had purchased the redundant pulpit from Emmanuel College and presented it to his church. It has been suggested that this was either at the behest of, or an attempt to please, the owner of Trumpington Hall, Sir Francis Pemberton. This is plausible, as Pemberton was an Emmanuel graduate, and had recently contributed £20 towards the costs of the new chapel. Yet there was another player in the story. The accounts for the fitting up of Emmanuel’s original chapel as a library, record that on 3 November 1679 the college received £5 from ‘Dr Linnet for the old Pulpit’. This was William Lynnet D.D., Fellow of Trinity College, and vicar of Trumpington from May 1679 until his death in 1693. Presumably, Thomas Allen reimbursed him. The elegant pedestal on which the pulpit now stands (replacing a cumbersome Victorian base) was presented in 1976 by Margaret Gardner in memory of her husband, Robert, who had served as churchwarden at Trumpington. ‘Bobby’ Gardner was, of course, a legendary figure at Emmanuel, holding the offices of Fellow and Bursar for many decades.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist

.JPG)