Blog

11 December 2024

The Christmas story is told in tinted drawings in one of the older of the medieval manuscripts in Emmanuel’s collection, some leaves from a Psalter (MS 250.2).

These were made around 1220-1230 in a workshop of London illuminators for the Benedictine abbey of Chertsey in Surrey. They are thus a little older than the church of the Cambridge Dominican friars, the church that later would be repurposed into Emmanuel’s present Hall. The Cambridge Dominicans are recorded to have received royal oaks for their church in 1238.

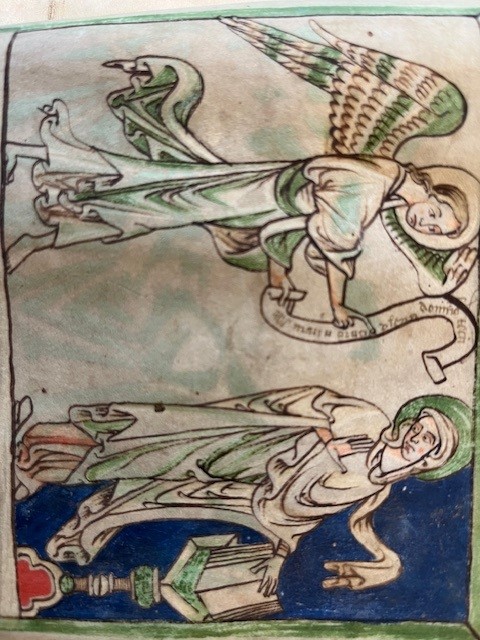

The story begins when an angel appears to Mary, telling her that she shall conceive a son, to be named Jesus, ‘and of his kingdom there shall be no end’. To Mary’s question ‘How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?’ the angel replies ‘The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee’ (Luke 1: 28-38).

The Annunciation. The angel’s scroll represents part of his speech. Interrupted at her reading, no wonder Mary’s gesture and averted gaze seem to convey astonishment at her destiny

The angel further tells Mary that her cousin Elizabeth, previously called barren, is already six months pregnant in her old age, ‘for with God nothing shall be impossible’. Mary hastens to visit her cousin, and when Mary comes in, Elizabeth feels her baby leap in her womb at Mary’s salutation, and cries out to Mary ‘Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb’ (Luke 1: 39-56).

The Visitation. Note the hand reaching forward towards the other woman’s womb

Joseph travels with his expectant wife Mary to Bethlehem in order to be taxed. But Mary is due to give birth, ‘and she brought forth her firstborn son and, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn’ (Luke 2: 1-7).

The Nativity. In medieval depictions Mary is sometimes shown, as here, turned away from her newborn baby to pursue her own thoughts. Joseph, leaning on a stick, wears the pointed hat that in medieval illustration indicates a Jewish man

Meanwhile, the angel of the Lord appears to shepherds keeping watch over their flocks by night, and tells of the birth of a Saviour, whom they will find lying in a manger (Luke 2: 8-20).

The angel, bearing a palm, addresses three shepherds, who stand on a stylized landscape of three hills with sheep – their dogs are very interested in the angel

‘Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem … behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem, saying, “Where is he that is born King of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him”’ (Matthew 2: 1-2).

Although guided by a star according to scripture, the artist shows the Magi – here depicted as crowned kings – in some confusion about the right direction to go

Rattled by this news of a rival Jewish king, Herod summons the wise men and sends them to Bethlehem to seek out the child, adding duplicitously ‘and when ye have found him, bring me word again, that I may come and worship him also’ (Matthew 2: 3-8).

A crowned King Herod, seated in a swaggering posture, and with a tiny page holding his sword before him, seems to be almost squeezing the crowned Magi against the righthand edge. (They are depicted, according to tradition, as representing youth, middle age, and old age)

‘Lo, the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was’. The wise men fall down and worship the child, presenting him with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh (Matthew 2: 9-11).

Adoration of the Magi. Mary is shown crowned and enthroned, holding up an orb from which a plant springs, while the three kings hold their gifts aloft

‘And being warned of God in a dream that they should not return to Herod, they departed into their own country another way’ (Matthew 2: 12).

Slumbering on luxurious pillows, the three kings have gone to bed while still wearing their crowns (as one does). But, contrary to scripture, the artist represents the youngest king awake to receive the angel’s warning

Joseph is similarly warned by an angel in a dream to flee with Mary and Jesus to safety in Egypt, beyond the reach of King Herod (Matthew 2: 12-15).

The Flight into Egypt. Joseph leads the donkey, with an assistant behind. Many apocryphal miracles became associated with this refugee journey

Then Herod – enraged ‘when he saw that he was mocked of the wise men’ – orders the massacre of all children under the age of two in the vicinity of Bethlehem (Matthew 2: 11).

The Massacre of the Innocents. Two knights wearing contemporary chainmail murder children in their mothers’ arms with sword and spear. To the right, Herod supervises, crowned and sceptred, and in a lordly cross-legged posture

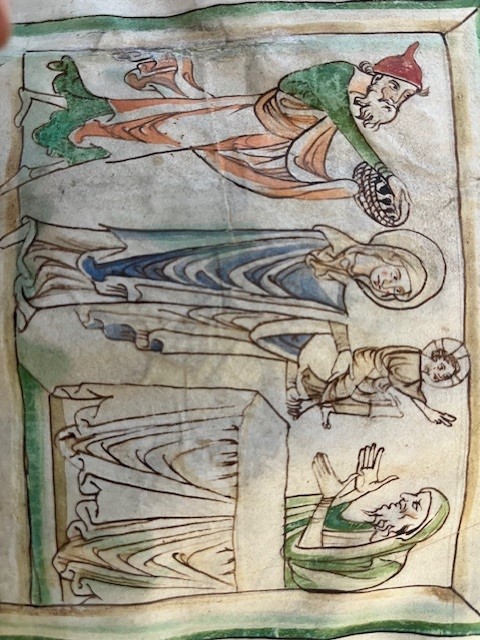

The Christmas story closes at Candlemas on 2 February, when Mary and Joseph present the child to the Lord in the temple. A devout old man, Simeon, to whom it has been revealed that he shall not die until he has seen Christ, takes the child in his arms, blessing God and uttering the words ‘Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace’.

Presentation in the Temple. Joseph carries an offering of doves

Although these fragile leaves, eight centuries old, visualize the Christmas story in some different ways than later art has shaped later imaginings of the episodes, they possess their own energy, directness and power.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books