Blog

5 March 2025

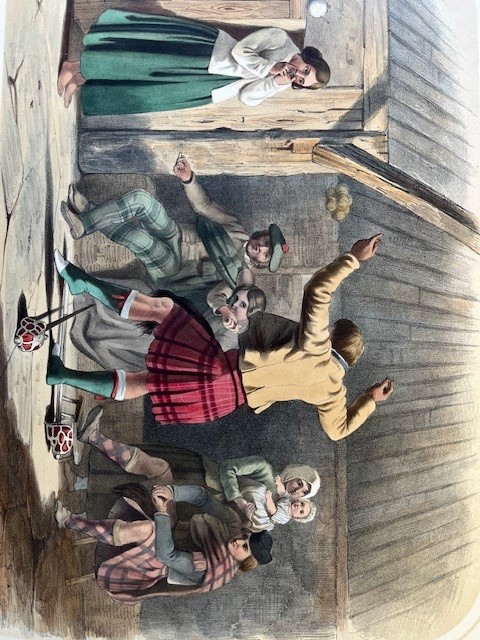

'Picturesque Gatherings', 'Gille Calum' (The Sword Dance)

'Picturesque Gatherings', 'Gille Calum' (The Sword Dance)

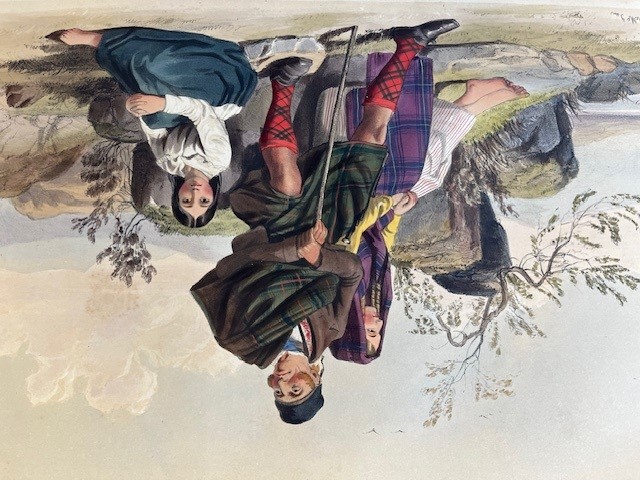

Both the Scottish Highlands and their inhabitants as objects of fascination is a development of the Romantic age. In 1775 Samuel Johnson could say that to the inhabitants of southern Scotland ‘the state of the mountains and islands is equally unknown with that of Borneo or Sumatra’. But factors such Sir Walter Scott’s immensely popular novels, and Queen Victoria’s love affair with the Highlands, changed all that. Robert Ranald McIan (1803-1856), who became an artist after an early career as an actor, saw a gap in the market. His Picturesque Gatherings of the Scottish Highlanders (1848) complains that while there are guidebooks to Highland scenery ‘the social state of the Celtic population of Britain is still … but little known’. In his vivid lithographs, McIan, a staunch Jacobite, celebrates and romanticizes how ‘the Gael have preserved a peculiar language, a singular garb, and a mode of life alike to the nomadic, pastoral state of the most ancient people.’

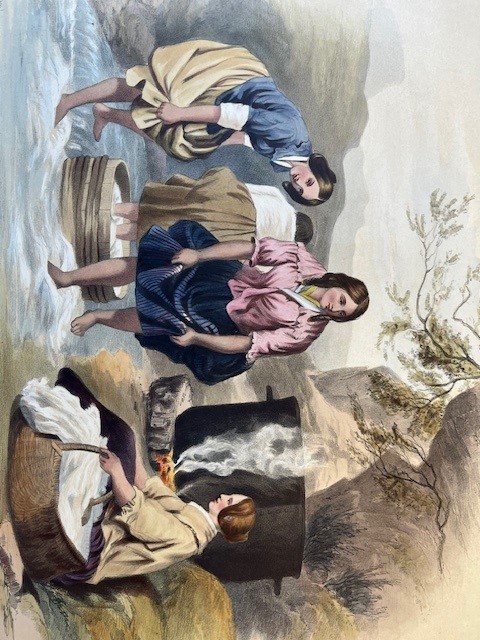

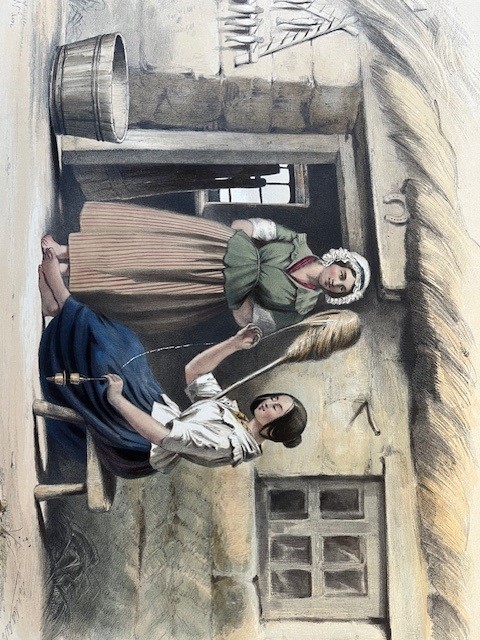

Viewing the Highlanders as survivors of an archaic society includes an emphasis on the prominent role of women in sustaining the community, through domestic activities like washing clothes and spinning.

'Washing Clothes'

'Spinning with the Distaff'

'Spinning with the Distaff'

Bulky items like blankets would be washed by being trodden by women in streams and rivers, often accompanied by singing. The text laments that the women engaged in spinning with a distaff have adopted some modern fashions, such as a cap, but do keep the old Highland ways in going without shoes (only worn, reluctantly, to church).

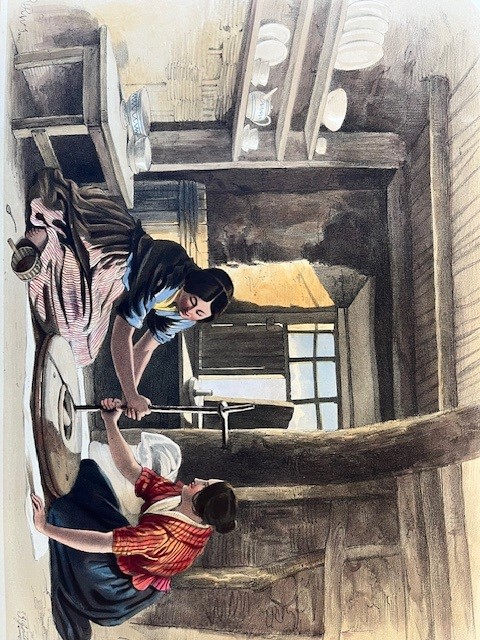

The women shown operating a hand mill within the home are engaged in a laborious process.

'The Hand-Mill'

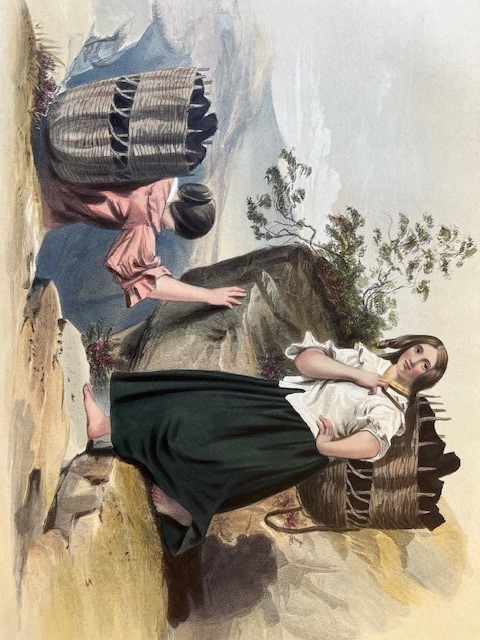

But other illustrations show women carrying out such arduous tasks as carrying in peat and ferns.

'Carrying Peat'

'Carrying Fern'

'Carrying Fern'

Peat and turf were the only materials available for burning on the hearths of the poor. Peat was cut in thin bricks and dried during the summer months, and the woman is shown carrying it in a ‘creel’ or basket. Helping neighbours with peat gathering sometimes became a communal activity undertaken in ‘a spirit of cheerful co-operation, such as a Socialist might envy’. Fern and bracken had many uses, from litter for cattle to use as a durable thatching material for dwellings.

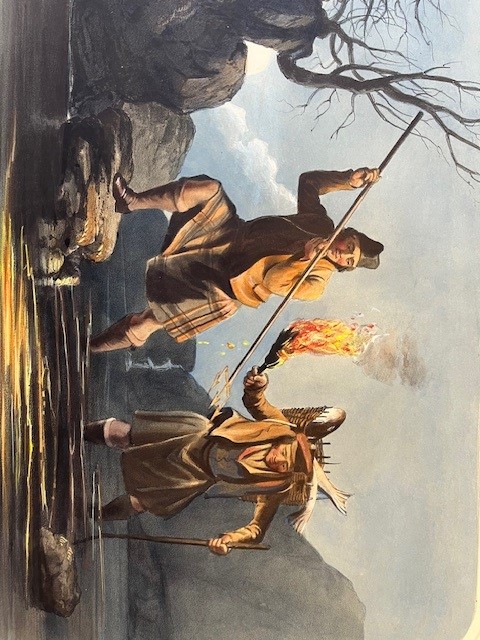

The traditional activities of male Highlanders can become instances of the picturesque in a different way. The spearing of salmon from small boats by night is a Highland custom that lends itself to a striking nocturnal image, while abseiling down a sheer cliff to steal eggs from an eagle’s nest, and be attacked by outraged eagles for one’s pains, provides an exciting action picture of derring-do.

'Spearing Salmon'

'Robbing the Eagle's Nest'

Behind many images is a pervasive nostalgia: the text laments over-fishing by net along the coast and predicts the speedy extinction of the salmon, elsewhere complaining about the presence of foreign fishing boats – themes that we seem to have heard more recently too.

An illustration of men threshing (note the refreshments ready in the foreground) remarks that close to this scene are buried twenty men slain in a confrontation in 1645 between the Earl of Argyll and the Marquis of Montrose, for there is always a sense of a landscape storied with past misfortunes.

'Threshing Corn'

'Threshing Corn'

'Drovers'

'Drovers'

The picture of some drovers refreshing themselves with brose (oatmeal and water) refers to their remarkable journeys, driving cattle from the Highlands to Smithfield, fattening the cattle in pastures in Lincolnshire and East Anglia on the way. These were Highlanders with wider horizons, who needed to speak English and to travel distances at their own expense until they could eventually settle up.

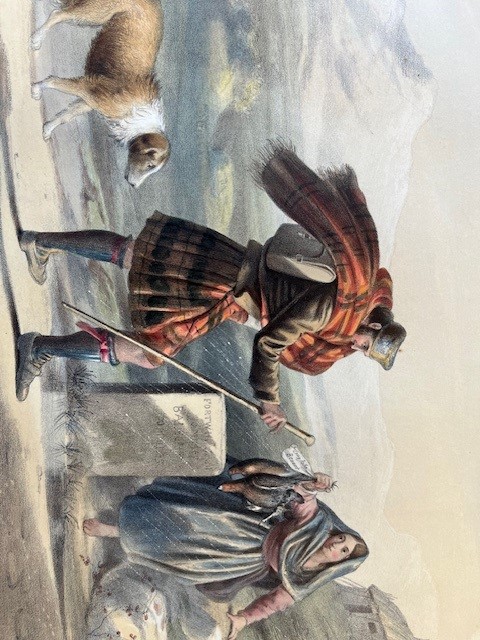

Distance was intrinsic to Highland life, and with it the difficulties in remaining connected, as suggested by the illustrations of fording a river and of a Highland postman.

'Fording a River'

'Highland Foot-Post'

The text describes how the Duke of Gordon employed a man both to deliver his messages and to bring back news and gossip, and no doubt this was the role of many messengers in a traditional society.

Subject to oppressive laws after their role in the Jacobite Rising of 1745, the Highlands long had an uneasy relationship with the law. The preparation of malt for private distillation was illegal, hence the secret stills for making whiskey (from the Gaelic 'Uisge beathe’ or water of life), hidden in caves and on moors.

'The Whiskey Still'

'Herring Fishing'

'Herring Fishing'

Whole neighbourhoods colluded in concealing distilling and smuggling activity from the hated excise men. In the illustration for preserving salted or smoked herring in barrels, the implication is that the barrels are actually being used to smuggle whiskey.

One illustration celebrates a Highland outlaw from an earlier age.

'Ewen MacPhee, the Outlaw'

'Ewen MacPhee, the Outlaw'

Ewen MacPhee deserted from a Highland regiment and, after being on the run, took refuge on a tiny half-acre islet in the Caledonian canal. Here he lived meagrely, married a fourteen-year-old wife and had five children, while grazing some goats on nearby land that did not belong to him. Eventually the goats were moved on, but not before Mrs MacPhee pursued the culprits, firing a gun. The islet was purchased by a landowner but, before he could do anything, Mr MacPhee called on the new owner and coolly but very politely informed him that he would never think of molesting him.

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books