Blog

5 March 2025

K is for … King James Bible

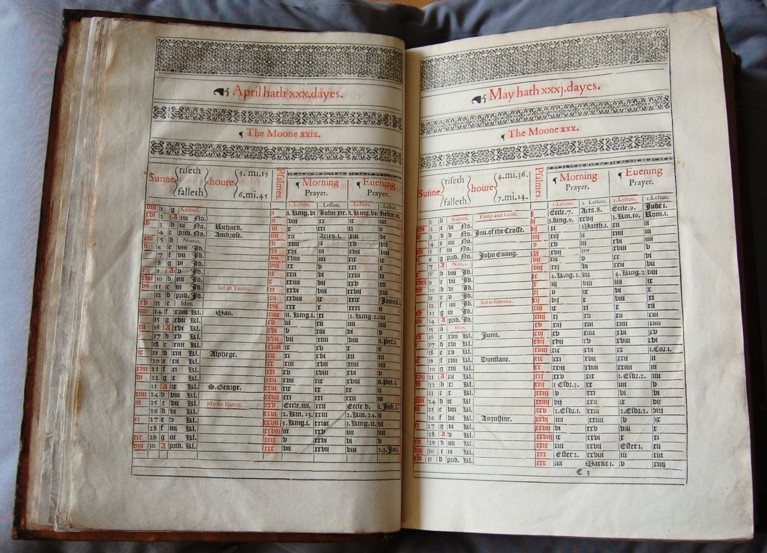

The ‘King James Bible’ is one of the most celebrated works in the English language. A new translation of the bible was sanctioned by James I and VI at the Hampton Court Conference of January 1604, a gathering to which Laurence Chaderton, Master of Emmanuel College, had been invited. One-third of the translation work was assigned to eminent Cambridge theologians, four of whom were connected with Emmanuel: Chaderton, of course, and current or former Fellows William Branthwaite, Samuel Ward and John Richardson. Chaderton and Branthwaite were part of the First Cambridge Company, responsible for translating I Chronicles to the Song of Solomon, while Ward and Richardson were in the Second Cambridge Company, working on the Apocrypha. A fifth Emmanuel man, William Eyres, assisted the First Company. The translators were unpaid, at least until the later stages of editing, but their dioceses or colleges were enjoined to give them financial support. The college accounts for the years following 1604 record the Emmanuel translators making frequent trips to London, where they no doubt divided their time between college business and Cambridge Company duties. The King James Bible was finally published in 1611, but the oft-quoted date of ‘2nd May’ is apocryphal. It was on sale by November, and the college records tend to support this later publication date, as an entry noting payment for ‘the new translated byble’ appears in the accounts for the half-year following 23 October 1611. The college paid 50s for the handsomely-bound volume, plus a carriage fee of 1/6. This bible is preserved in the library’s rare books collection. It is a superb first edition ‘He-bible’, so-called because of an ambiguity in the Book of Ruth that was quickly altered to ‘She’ in subsequent printings. A double page from the almanac section is pictured.

K is for … Kitchens

.jpg)

The kitchens may not be the spiritual heart of the college, but they have been fundamental to the contentment and good health of countless generations of residents. In the early period of Emmanuel’s history, the domestic affairs of the college were under the overall control of the Steward, who was always a member of the Fellowship. The day-to-day running of the kitchens, though, was in the hands of the manciple, who had charge of the keys of the pantry and buttery, kept the accounts, and dealt with ‘the baker, the brewers and the butchers’. The earliest kitchen inventory was made in 1589. This recital of archaic battery ware opens with the entry: ‘One great brass pott geven by our Founder’, and goes on to list such things as a ‘possnett’, a ‘Minsing Knyff’, beef and mutton spits, a ‘Cliver’, pot-hooks, a ‘little kettle with three feet’, a ‘grydiron’, mortars, pestles, chafers and trivets. Meals were prepared by the senior cook, with the assistance of an under-cook, whose duties included washing-up. They employed their own scullions (popularly known in Cambridge as ‘skulls’), who did the really menial work. In 1613, two undergraduates were disciplined for ‘pumping the skull twise’, an unpleasant piece of horseplay that involved drenching the scullion under the kitchen pump. This misdemeanor was aggravated by the fact that it involved trespass, for a college order of 1588 had forbidden students from entering the kitchens. The rambling complex (pictured) was, nevertheless, the setting for several brawls, presumably because it offered budding ruffians a sporting chance of evading the watchful eyes of the Fellows, who made regular patrols. A more serious affray was the college ‘Riot’ of 16th April 1742, when many windows, including some in the kitchens, were smashed. The participants were disciplined and the two ringleaders rusticated.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist