Blog

2 April 2025

Bolton Priory, in W. Richardson, 'Monastic Ruins of Yorkshire'. In his 'Modern Painters' (1856), John Ruskin writes of 'the sweet peace and tender decay of Bolton Priory'

The sight of ruins has the power to prompt both melancholy and also a curious kind of pensive pleasure in contemplating the transience in all human and material creation that ruins may represent. In 1953 the novelist and travel-writer Dame Rose Macaulay published her study The Pleasure of Ruins, now seen as pioneering and seminal in subsequent academic studies of how ruins are perceived in very different cultures across the world. In the Edinburgh Review in 1840 Dame Rose’s relative, Thomas Babbington Macaulay, had imagined a future traveller from New Zealand sketching the ruins of St Paul’s Cathedral from a broken arch of London Bridge amidst a totally ruined London (with the ruins of Rome and its once great empire in mind).

William Richardson’s The Monastic Ruins of Yorkshire (1843) is in two enormous and heavy volumes, profusely illustrated with large lithographed plates (up to 50 x 32 cms), plans, and drawings of architectural details, in chapters devoted to each religious house. Like other books in Emmanuel’s Graham Watson Collection, Richardson’s work testifies to the special place of ruins in the contemporary taste for the picturesque. The Monastic Ruins is also patriotically Yorkshire, published in York and dedicated to the Archbishop of York. The venerable antiquity of Whitby Abbey’s foundation earns it first place at the start of the volumes.

Whitby Abbey: 'one of the most moving ruins in England, on its bare, wind-swept hill ... The weathering helps enormously to enforce the peculiar ruin qualities' (Pevsner, 'Yorkshire: The North Riding')

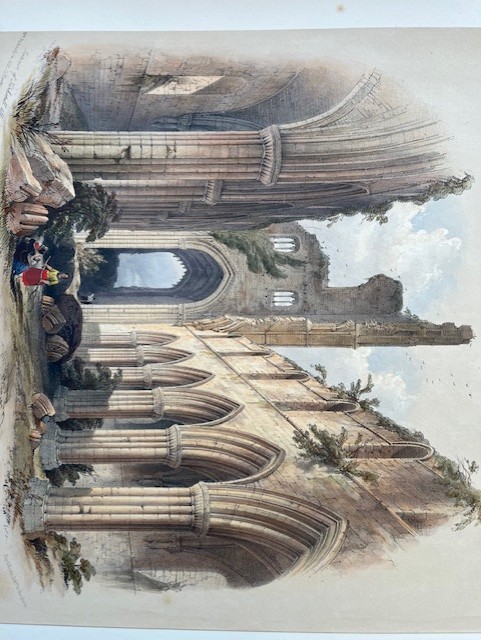

The witness of ruins as the remaining fragments of what was once complete and functioning prompts the imagination to try and reconstruct these buildings in the mind, making up for what has been lost. This can be so with the most minimal surviving ruins, but it is perhaps even more the case where much remains, as in the towering ruins of Kirkstall Abbey.

Kirkstall Abbey

When the Dissolution of the Monasteries was barely beyond living memory Shakespeare could refer to ‘Bare ruined choirs, where once the sweet birds sang’ (Sonnet 73), exemplified by such lofty but abandoned and roofless spaces as at Kirkstall and at Fountains Abbey (the best preserved of English monastic ruins).

Kirkstall Abbey

Fountains Abbey: 'Oh what a beauty and perfection of ruin!!' (The Hon. John Byng, quoted in Pevsner, 'Yorkshire: The West Riding')

By the eighteenth century the appeal of ruins was such that the makers of landscape gardens sometimes actually created fake ruins as eye-catchers and prompts to reflection. There was no need for this at Fountains or at Rievaulx Abbey, where genuine ruins could be incorporated as features within created landscapes. Fountains Abbey served as the climactic coup de theatre at the end of the garden at Studley Royal, while Rievaulx could be contemplated from above, from a grassy terrace complete with Classical temples.

Rievaulx Abbey. 'When it was all complete ... It must have been a glorious sight, as imposing as any castle and so much more regular and orderly and civilized ... For the picturesque traveller it is an exquisite feast ...' (Pevsner, 'Yorkshire: The North Riding')

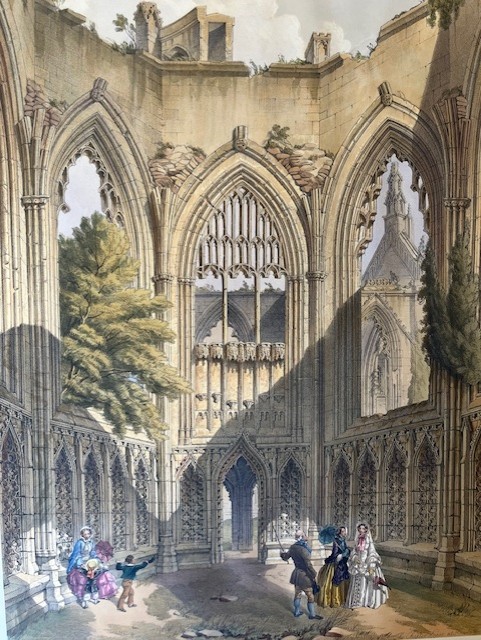

Before modern curatorship, that aims to arrest further deterioration and ‘freeze’ the ruin at its present state for the future, part of the melancholy pleasure in ruins was that their further decay, perhaps into complete oblivion, seemed inevitable. Sometimes – as in Richardson’s plate of the remaining ruin at Guisborough Priory – the picture includes pensive human figures. Sometimes the ruins are being inspected by well-dressed Victorian tourists, as in his plate of the chapter house at Howden, where the roof had collapsed as recently as 1750.

Guisborough Priory

Howden Church: chapter house. 'it is in ruins, as is the chancel, and in fact it makes a fine ruin' (Pevsner, 'Yorkshire: York and the East Riding')

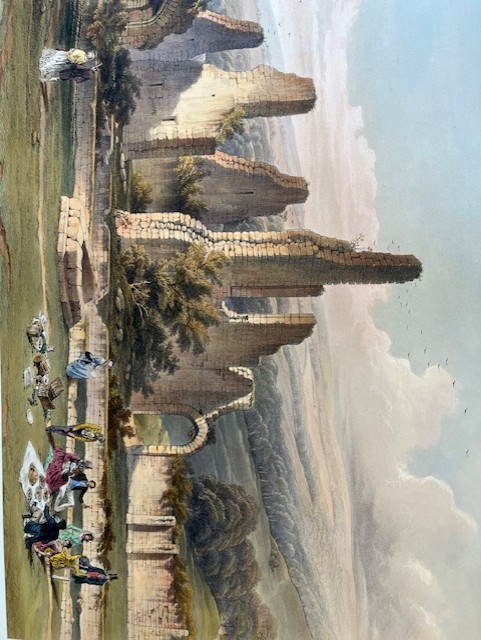

Richardson’s plate of Sawley Abbey shows an early Victorian family enjoying a picnic on the grass during a visit to the ruins (note a very large pork pie), but in the background is a glorious landscape which was no doubt also part of their day out, a landscape into which the ruins might eventually be absorbed.

Sawley Abbey

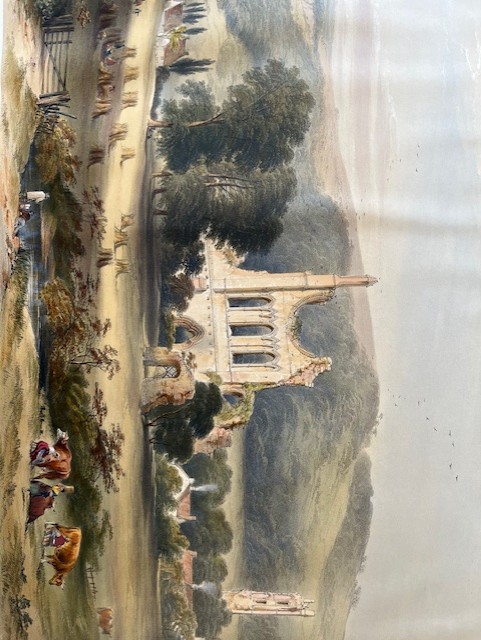

Easby Abbey: 'one of the most picturesque monastic ruins in the county richest in monastic ruins' (Pevsner, 'Yorkshire: The North Riding')

The ‘bare ruined choir’ of Easby Abbey – with vegetation sprouting everywhere from the masonry and with tumbled stones – might suggest that these ruins are well on the way to becoming part of the natural landscape again. The number of Richardson’s plates that show cattle grazing near or amongst the ruins – even if these are cows very aesthetically grouped for picturesque effect – suggests how the ruins are being taken back into the countryside.

Richardson’s plates of Byland Abbey, with its shattered rose window rising above the Yorkshire landscape, is a striking image of a ruin’s power to summon up something that is gone yet still imaginable in the mind’s eye.

Byland Abbey

The concentration of images of ruined splendour in Richardson’s Monastic Ruins confronts any reader with the sheer scale of destruction and prompts, even now, guilty regret at such cultural vandalism and nostalgia for what is lost. As Byron wrote in Don Juan:

A grey wall, a green ruin, rusty pike,

Make my soul pass the equinoctial line

Between the present and past worlds … (Canto X)

Barry Windeatt, Keeper of Rare Books