Blog

29 October 2025

R is for … Railings

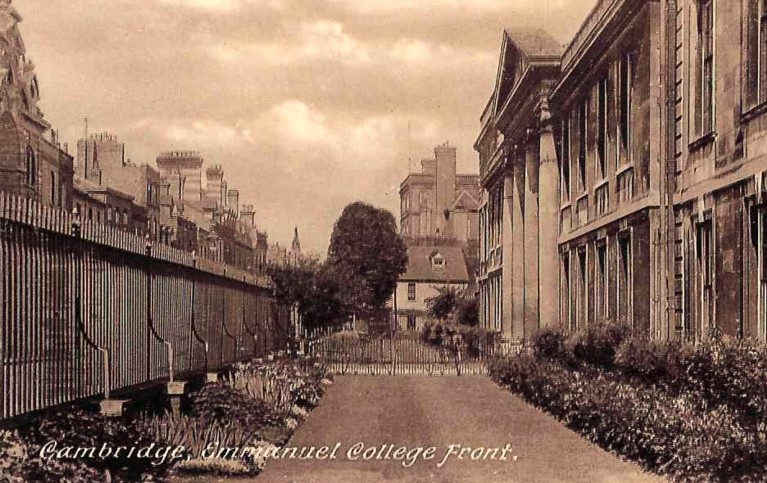

When Emmanuel’s western frontage, the Essex Building, was erected in the 1770s, it was deliberately set back from the busy highway of St Andrew’s Street. A low brick wall with stone coping, topped by high iron railings, gave a further measure of protection. They can be seen in this 1931 postcard, recently donated by an old member of Emmanuel. The railings fronting the college today are not the Georgian originals. In the summer of 1940, in response to the wartime appeal, the college sacrificed most of its railings, including the stretch along St Andrew’s Street. The Master, ‘Timmy’ Hele, thought this made ‘an immense improvement’ to the college’s appearance, telling a correspondent that ‘our forebears did like iron, and their love of iron has put quite a nice little store at the disposal of the government’. Would that it had! After the war, the college bursar was told on the Q.T. that the railings had got no further than a scrap yard near Wisbech. With its protective ironwork gone, the college frontage was very exposed, although shrubs and saplings planted in the slips provided some screening. When Lord St John of Fawsley became Master of Emmanuel in the early 1990s, he was keen to restore the ‘handsome’ railings that had formerly ‘set off the Essex façade’ and afforded ‘much needed protection to the gardens behind’. A generous benefactor offered to fund the project. Planning regulations required that the new railings replicate the originals as closely as possible, so old engravings and photographs were scrutinised. The new ironwork was installed in 1997, to general approval. The trees planted in the slips after the war eventually succumbed to honey fungus and were felled in 2008, but this has allowed the elegance of the railings to be fully appreciated.

R is for … Regicides

The term ‘Regicide’, in respect of King Charles I, refers to the 59 signatories to his death warrant, and selected others who had played an active role in his arraignment and execution. An eighteenth century engraving in college’s print collection (pictured) shows the King’s trial. Emmanuel College, to its credit or otherwise, supplied three of the six Cambridge University regicides. These individuals, all of whom signed the death warrant, were William Purefoy (admitted 1598), Augustine Garland (1618) and Thomas Scot (1619). Purefoy, although a Calvinist, never took holy orders, preferring a career in politics and the army. In August 1659 he was ordered to suppress Sir George Booth’s royalist uprising, despite the fact that, as fellow regicide Edmund Ludlow put it, he had ‘one foot in the grave’. Colonel Purefoy did in fact die the following month, thus escaping retribution after the Restoration of Charles II. Following the monarch’s return in 1660, all the surviving regicides who could be tracked down were apprehended and tried for treason, including Thomas Scot, who had fled to Brussels. Augustine Garland was also arrested, but claimed that he had only signed the death warrant under acute pressure and fearing his ‘own destruction’. This plea was convincing enough to save his life, but he was sentenced to exile in Tangier. Scot was cut from a different cloth and remained defiantly unrepentant to the end. For him there could be no mercy, and he was hanged, drawn and quartered in October 1660. Garland and Scot may have encountered a familiar face during their imprisonment, as one of Commissioners appointed to try the regicides was the Royalist judge, Sir Christopher Turnor, who had been admitted to Emmanuel in 1623. Some years later, Turnor gave his old college £10 towards the building costs of Wren’s chapel.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist