Blog

5 December 2025

Image caption: A gloomy corner of the college kitchens, c.1950

It is, of course, customary for Emmanuel’s kitchens to close over Christmas and New Year, a policy accelerated in the early twentieth century by the steadily dwindling number of resident Fellows. Kitchen menu books of the 1920s and 30s show that no meals were served later than lunch on Christmas Eve, and that the kitchen staff did not return to work until early January.

This civilised arrangement came to an abrupt end upon the outbreak of the Second World War. North Court was taken over by the military for the duration, and as the servicemen’s meals were prepared by Emmanuel staff, the kitchens were obliged to stay open all year round. The Christmas newsletters sent to old members in 1942 and 1943 lament the consequences: ‘short rations, staff changes, no vacations…we stagger from domestic crisis to domestic crisis’. The principal strain fell on the catering manager, Mary Bolt, whose kitchen workforce consisted mainly of untrained young women who decamped to better-paid jobs at the first opportunity.

As far as members’ meals were concerned, the only concession made to the kitchen staff on Christmas Day was that they did not have to cook a hot dinner. The handful of resident students and Fellows living in college were certainly provided with an evening repast, but it consisted of a simple buffet of cold cuts, potato salad and dessert, laid out in the afternoon. There had been a decent mid-day meal, though; the 1940 Christmas Day luncheon, for instance, comprised roast chicken, sprouts and baked potatoes, followed by mince pies. The menu in the succeeding three years was identical, except that Christmas pudding replaced mince pies.

In 1944, when the war was nearing its final stages, the kitchens were able to close for four days over Christmas, and the following year the staff had eight days off. A note of festivity returned to the menu books, too, as the evening meal served on 21st December 1945 was described as ‘Xmas dinner’, a title not applied to anything served during the war. This did not, sadly, indicate a more sumptuous meal, as the bill of fare was virtually indistinguishable from the wartime Christmas Day lunches. The only touch of luxury was that the potatoes were roasted, not baked.

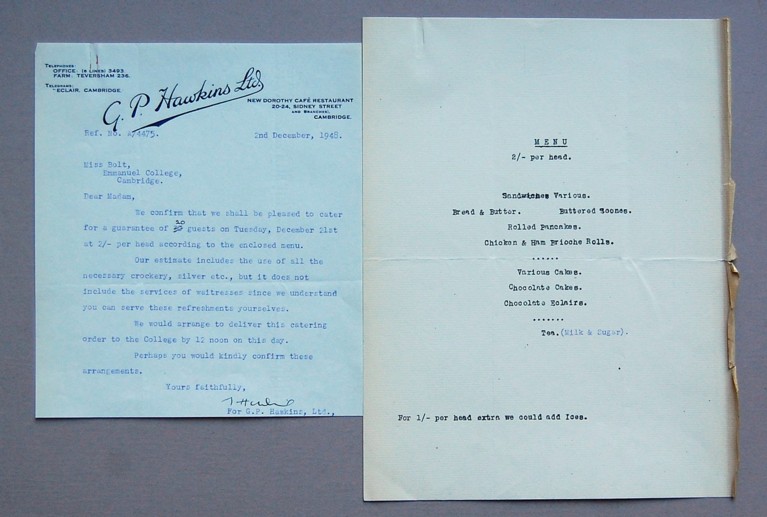

Image caption: Letter and menu for the college Christmas tea-party, 1948

The war might have been over (we have of course celebrated the 80th anniversary of its ending this year), but rationing continued, and it was several years before normal college hospitality was resumed. One of the earliest festive occasions was the dinner party hosted by Professor Ronald Norrish (one of Emmanuel’s three Nobel Prize winners) on Saturday 18th December 1948. Norrish was famed for his hospitality, and the guests stayed late into the night. Kitchen staff could leave, though, once they had cleared the dining table of all the food, plates and silverware. The porter on duty was instructed to check the gallery after everyone had gone, ‘and satisfy himself that no cigarette ends etc are left which could possibly cause a fire’. Different times! Three days later the college put on a Christmas tea party, presumably for the Fellows, but this did not involve extra work for kitchen staff, as the catering was provided by G P Hawkins of Sidney Street. The menu (shown above) sounds tasty enough, and although the chocolate eclairs may not have contained real cream, or indeed much chocolate, things were beginning to look up.

[The title of this piece derives from George Robert Sims’ famous Victorian poem, Christmas Day in the Workhouse, so beloved of the late Joe Grundy Esq of Ambridge. Sims’s melodramatic monologue has been much parodied, and at least two versions of Cookhouse are known, one of them featuring in the film Oh! What a Lovely War]

Amanda Goode, College Archivist