Blog

20 January 2026

T is for…Tankards

Emmanuel’s plate collection contains several seventeenth-century tankards, a term then applied exclusively to mugs with a hinged lid. The earliest reference in the archives to one of these heavy pots occurs in 1620, when ‘Dr Branthwaites guilded Tankard’ is listed in a plate inventory. William Branthwaite, sometime Fellow of Emmanuel, was Master of Caius College at the time of his death, in 1619. Under the terms of his will, he bequeathed to Caius and Emmanuel identical drinking mugs, described as a ‘silver tankard pott, gylte, with my armes on it’. Emmnanuel’s early seventeenth-century ‘Benefactor’s Book’ assigns Branthwaite’s ‘chalice’ a value of £8, so it is not surprising that the tankard was stored in the Treasury, with other precious silver-gilt ware. Pewter tankards became widely used by students and Fellows alike during the 1620s, and many are listed in college plate inventories under the name of their owner (every member had his own personal drinking vessel). By the late-seventeenth century, though, unlidded ‘quart cans’ were becoming the fashion. This change in taste, as much as wear-and-tear, eventually led to nearly all the college tankards being melted down and re-fashioned. Branthwaite’s precious silver-gilt pot managed to survive until at least 1818, but it had gone by 1843. Half a dozen or so tankards did, however, escape the crucible. Ranging in date from 1675-1765, they are all inscribed with the names of their student owners, or rather donors, as the individuals involved were fellow commoners, who were obliged to present a piece of silverware to the college soon after their admission. Tankards enjoyed a renaissance in the nineteenth century, when they became popular as student sporting prizes. Several such trophies are held in the college Museum collection, including the Trial Eights tankard of 1875 pictured above.

T is for…Tunnel

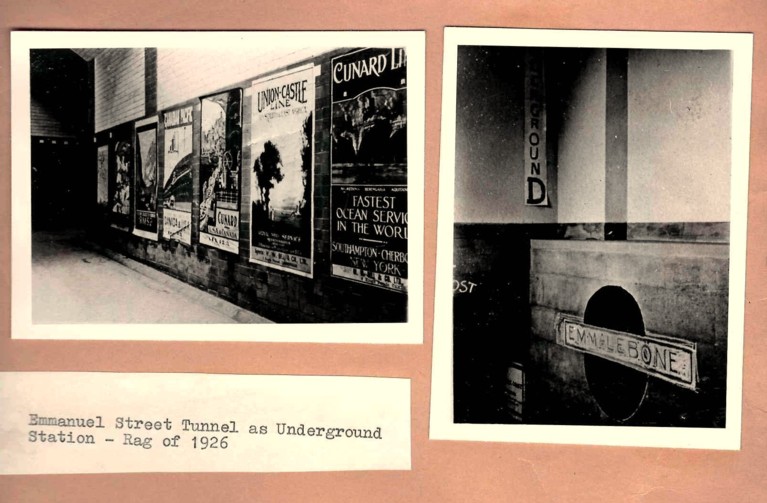

Emmanuel is thought to be the only Cambridge college to have an under-road tunnel. Lined with Edwardian green and white glazed ceramic tiling, it is a much-loved feature of the college. The tunnel was constructed in conjunction with North Court, in the years immediately preceding the First World War. The City Council had previously agreed to sell Emmanuel Street to the college, so that the planned new court could be seamlessly integrated into the college precinct, but a change of policy resulted in the council providing a tunnel instead. Incidentally, the architect of North Court, Leonard Stokes, invariably referred to the underpass as a ‘subway’, presumably because it was intended solely for pedestrian, and not vehicular, use. In the mid-1950s, however, the college started calling it a ‘tunnel’, and this is now the preferred term. When Emmanuel Street was widened in 1968, the underpass had to be extended at its northern end, and although the new tiles matched the originals as closely as possible, the join is not difficult to spot. The dramatic possibilities offered by the tunnel’s echoing acoustics and diagonal orientation have not been overlooked. A theatrical production, Roseleaf, was staged there in 1993, and the tunnel also served as part of the ‘Northern Line’ for the 2013 May Ball, the theme of which was ‘Last Call to London’. The tunnel’s resemblance to a London Underground station had been exploited as early as 1926, resulting in ‘one of the best rags ever perpetrated’. During the Long Vac, a group of Emma medics decorated the underpass with genuine railway posters, procured from Cambridge station by Julius Summerhays (1925). A mock station sign, ‘Emmalebone’, was painted directly onto a wall (see image above). This proved difficult to remove, earning Summerhayes an ‘avuncular’ rebuke from the Senior Tutor, P.W. Wood.

Amanda Goode, College Archivist